Post: A Tutorial for Natural Language Processing

Motivation and background

I did a 3 month internship at a Fortune 500 company working on a Natural Language Processing project having had no familiarity with this field prior to my first day at the office. As a result, I went through a self-taught crash course to improve my understanding. I had numerous false starts and at times was overwhelmed with the content I had to understand, but eventually managed to complete my project successfully.

Because of this experience, I want to share what I learned during this time. Ideally, I would just be able to upload the actual project itself, but I am not allowed to share that information from a legal point of view. As a result, I created this guide which covers:

- A bird’s eye view of NLP in the context of Sentiment Analysis & Text Classification

- Tokenising and Pre-processing textual data

- Methods of text vectorisation, also known as feature representation

What is NLP and how does it fit into a machine learning context?

NLP is a special field that exists at the intersection of linguistics, computer science and machine learning. It aims to use computational resources to process and analyse human speech, then perform a specific task. Some of the more popular such tasks are text summarisation, semantic text similarity, part-of-speech tagging and sentiment analysis.

Since I did a sentiment analysis project, I will focused on this task. Sentiment Analysis involves using ML algorithms to elicit the sentiment behind some textual data. In other words, its aim is to look at a piece of text and tell us whether the emotion conveyed by the text is positive, negative or neutral as a first level of analysis. A second level of analysis may also be pursued, which would inform us about specific emotional connotations, such as anger, disgust or love, textual data may have. As we are sorting data into different ‘labels’, this is a supervised learning classification task

There are obvious applications for NLP in a commercial setting. For sentiment analysis specifically, businesses that encourage their customers to review them may quickly want to understand the general sentiment attached to the text without having to go through thousands of reviews manually. Badreesh Shetty’s excellent article on Medium provides a list of other NLP applications (the links to the services he mentions are present in his article):

- Information Retrieval (Google finds relevant and similar results).

- Information Extraction (Gmail structures events from emails).

- Machine Translation (Google Translate translates language from one language to another).

- Text Simplification (Rewordify simplifies the meaning of sentences).

- Sentiment Analysis (Hater News gives us the sentiment of the user).

- Text Summarization (Smmry or Reddit’s autotldr gives a summary of sentences).

- Spam Filter (Gmail filters spam emails separately).

- Auto-Predict (Google Search predicts user search results).

- Auto-Correct (Google Keyboard and Grammarly correct words otherwise spelled wrong).

- Speech Recognition (Google WebSpeech or Vocalware).

- Question Answering (IBM Watson’s answers to a query).

- Natural Language Generation (Generation of text from image or video data.)

Let’s take a quick look at the pipeline of a project, which is informed mostly by my personal experience and may differ for different tasks and domains

1) Pre-processing

For the first step, we want to tokenise our text data. To tokenise text is to split bodies of text into chunks, usually single words, that are better processed by a computer. It is easier for a machine to deal with single words than with large sentences. Why this is the case requires depth that I aim to avoid in this bird’s eye view post.

Next, we want to process our text data in such a way that it makes it as easy as possible for a machine to pursue the goal we have assigned it. What does this mean? Suppose you have two reviews, and your human brain tells you one is inherently positive in nature and the other is negative. You also notice that both reviews have a lot of words that are not particularly indicative of the sentiment of the tweet. Words like ‘the’, ‘a’, pronouns, ‘who’, ‘what’ and so on fall into this category.

When a machine looks at these two reviews and their given labels, it notices that both reviews have such words, yet the labels attached to the reviews are different. In this way, its ‘learning’ is negatively affected because these words cannot differentiate between the ‘good’ review and the ‘bad’ review.

It could be in our interest, therefore, to remove or filter out such words, called stop words, so our algorithms can get to the meat of the text more easily, the ‘meat’ being words that are emotionally indicative, such as ‘suffer’ (a review containing the word ‘suffer’ is more likely to be negative than one that does not contain that word). These words will very likely be unique to either review, and so the machine is better at ‘learning’ these connotations. However, it is important to note that this specific step, removal of stopwords, should be considered on a case-by-case basis, as its cons can outweigh the pros. I consider this point of view in the next post of this series.

Stop words are just one aspect of pre-processing. This step is covered in greater depth in the next part of this blog post

2) Train-test split

This step is very familiar to its counterpart in classical, non-NLP ML tasks. We split our processed, vectorised data into a training set and a test set, with the option of subdividing the training set into a validation set also.

3) Feature representation and transformation

Now we must ensure that our text data is in a format that a computer can read. Computers can only understand binary language which is numerical in nature. Consequently, we need a way of converting text data into numbers that maintains the meaning of the text in some way. This process is called vectorisation.

Just as there exists a wide array of ML algorithms for regression, classification and clustering tasks, there are many ways to convert text into numbers. For the purpose of this series of posts, I will cover the following, which are ranked in increasing order of sophistication:

- Bag of Words or BOW

- Term frequency–inverse document frequency or TF-IDF

- Word Embeddings (with a focus on Word2Vec and GloVe)

We must keep in mind that new advances in NLP are being made every day, so this list is by no means addresses state of the art approaches. But for many tasks, the vectorisation methods mentioned here perform well.

4) Training, testing and evaluating models

We train our models on the training set, tune them using the test set and usually evaluate the best performing model on the test set. If an NLP task is classification-based in nature, we use classification-based evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision and recall. A confusion matrix may also be used. It is important to note that there is a wide variety of problem types within NLP and therefore many other evaluation metrics are also used.

One thing to be aware of is that not all of the algorithms available to us in non-NLP tasks can be used for text classification specifically and NLP in general.

A Primer On Pre-processing

In the previous post of this series, I wrote about how pre-processing is the first step we should take when analysing text data. This is done so that we may maximise the performances of our algorithms based on the task we want to accomplish. Specifically, we want to filter out any aspect of the data that will at worst hinder and at best not be helpful in achieving our task.

The following is non-exhaustive roadmap that I consulted in my sentiment analysis project:

- Remove stopwords (context dependent)

- Stemming and lemmatisation

- Remove hashtags, mentions and emojis with text they represent (for Twitter)

- Replace contractions with their full forms

- Remove punctuations

- Convert everything to lowercase

- Remove HTML tags if present

Let’s take a look, with code, how these steps can be executed. To better frame this analysis, we will be using Amazon Product Data for their videogames category by Julian McAuley (Ups and downs: Modeling the visual evolution of fashion trends with one-class collaborative filtering R. He, J. McAuley WWW, 2016, found at http://snap.stanford.edu/data/amazon/productGraph/categoryFiles/reviews_Video_Games_5.json.gz)

This data contains the following useful variables:

- body of the review

- a ‘summary’ or review title

- an overall product rating out of

- the reviewer’s username

1) Deciding if we want to remove stop words using spaCy

Words that do not hold a lot of semantic connotation, and thus are not useful for linking input (text data) to output (semantic label) are considered stopwords. These include ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘who’, ‘why’, pronouns and so on.

However, we must be very careful in deciding whether or not to pursue this step, especially in the context of sentiment analysis. This is because removing stopwords may subtract from the true meaning of a sentence and thus alter it considerably. Consider the word ‘not’. “I do not like this colour” has the opposite sentiment of “I like this colour”. So if we remove the word ‘not’ from a review, we have effectively reversed the sentiment of the view.

As a result, in the context of sentiment analysis, it is advised to not execute this step. I will still display how to remove stopwords as a matter of demonstration. We can use a very useful NLP module called spaCy to do this.

# The data provided is in JSON format, so we can load it in a pandas dataframe using the following code:

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_json('/Users/alitaimurshabbir/Desktop/reviews_Video_Games_5.json', lines=True)

data.drop(['asin','unixReviewTime', 'reviewTime'], axis = 1, inplace = True) #drop unnecessary columns

data.head(2) #preview data

| reviewerID | reviewerName | helpful | reviewText | overall | summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | A2HD75EMZR8QLN | 123 | [8, 12] | Installing the game was a struggle (because of... | 1 | Pay to unlock content? I don't think so. |

| 1 | A3UR8NLLY1ZHCX | Alejandro Henao "Electronic Junky" | [0, 0] | If you like rally cars get this game you will ... | 4 | Good rally game |

spaCy comes with its own defined set of 312 stopwords. We can use this predefined list to remove stopwords from our reviews. It is useful to know that we can add our own stopwords to such a set (https://spacy.io/usage/adding-languages/#stop-words) so let’s go ahead and import spaCy and execute this step

import spacy

spacy.load('en') #load the English language model of spaCy

stopWords = spacy.lang.en.STOP_WORDS #load stopwords

#to see a few examples of these stopwords, I can convert the first 10 elements of this set into a list

stopList = list(stopWords)[:10]

print(stopList)

['how', 'meanwhile', 'four', 'make', 'as', 'becomes', 'anything', 'third', 'on', 'in']

Removing stopwords from our reviews using list comprehension

data['reviewTextNoStopwords'] = data['reviewText'].apply(lambda x:' '.join([word for word in x.split() if word not in stopWords]))

You will notice that we use the methods join and split.

We use them because pre-processing has to be performed on items in a list, not on a string. So split() is used to accomplish this. Subsequently, join(), is used to turn back the split components into a sentence/string, once a pre-processing step has been performed

Below is a comparison of the review text pre- and post-removal of stopwords.

data.loc[[0, 1, 2], ['reviewText', 'reviewTextNoStopwords']]

| reviewText | reviewTextNoStopwords | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Installing the game was a struggle (because of... | Installing game struggle (because games window... |

| 1 | If you like rally cars get this game you will ... | If like rally cars game fun.It oriented "E... |

| 2 | 1st shipment received a book instead of the ga... | 1st shipment received book instead game.2nd sh... |

2) Lemmatisation using NLTK

Lemmatisation is the process of reducing inflectional forms and sometimes derivationally related forms of a word to a common base form. The lemma of ‘walking’, for example, is ‘walk’. As with removing stopwords, lemmatisation is intended to improve model performance, although it is again possible that performance actually declines instead. This is because both of the aforementioned steps are intended to improve the recall metric and it tends to negatively impact precision. As a result, using either technique depends on the metrics one is focused on.

As with stopword removal, I will demonstarte how lemmatisation is achieved. We can use another very useful NLP module, called NLTK, and its function, WordNetLemmatizer()

import nltk

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

data['reviewText'] = data['reviewText'].apply(lambda x:' '.join([lemmatizer.lemmatize(word) for word in x.split()]))

3) Removing hashtags and mentions (Twitter-specific) using Regex

One of the cool things about NLP is that sources of data can be very specific in terms of the quirks they have. Sometimes we must deal with those quirks and sometimes we can leave them be. Data from Twitter, for example, will contain hashtags (#) and mentions (@username) because those mechanics are inherent to the platform. They are also not particularly useful in analysis, so we can remove them.

Doing so requires familiarty with yet another great module named Regex, or Regular Expression. Regex has special considerations for social media regular expressions and for Twitter in particular

Two such expressions in which we are interested are:

- @[A-Za-z0-9]+ which represents all kinds of mentions

- #[A-Za-z0-9]+ which represents all kinds of hashtags

Since our Amazon data doesn’t have many hashtags or mentions, let’s create a single string containing these elements and witness how Regex works. We will be using the join, sub and split string methods

import re

someText = '''Inter Milan goalkeeper @Samir Handanovic will not be #going to PSG. his agent @massimo venturella said

to football italia: "I can confirm that there were negotiations with PSG, which we have broken off. PSG is not an

option. Real Madrid and Liverpool are the other strong rumours. #inter #lfc'''

someText = ' '.join(re.sub( "(@[A-Za-z0-9]+)|(#[A-Za-z0-9]+)", ' ', someText).split())

print(someText)

Inter Milan goalkeeper Handanovic will not be to PSG. his agent venturella said to football italia: "I can confirm that there were negotiations with PSG, which we have broken off. PSG is not an option. Real Madrid and Liverpool are the other strong rumours.

4) Remove URLs using Regex

We can remove URLs in the same way we removed mentions and hashtags. This time the expression needed is \w+:\/\/\S+!, which represents all URLs matching with http:// or https://

5) Remove punctuations using Regex

As before, Regex makes this very easy. We use the expression .,!?:;-= to represent punctuations

data["reviewText"] = data['reviewText'].str.replace('[^\w\s]','')

6) Remove HTML tags using Beautiful Soup

This is very simple and self-explanatory. Our someText variable above does not have HTML tags, so the following shows a general way to accomplish this step

#textVariable = BeautifulSoup(textVariable).get_text()

7) Lower-case all text

data['reviewText'] = data['reviewText'].apply(lambda x: ' '.join(word.lower() for word in x.split()))

As seen below, all text can been converted to lowercase

data['reviewText']

0 installing the game wa a struggle because of g...

1 if you like rally car get this game you will h...

2 1st shipment received a book instead of the ga...

3 i got this version instead of the ps3 version ...

4 i had dirt 2 on xbox 360 and it wa an okay gam...

...

231775 funny people on here are rating seller that ar...

231776 all this is is the deluxe 32gb wii u with mari...

231777 the package should have more red on it and sho...

231778 can get this at newegg for 32900 and the packa...

231779 this is not real you can go to any retail stor...

Name: reviewText, Length: 231780, dtype: object

8) Replace contractions with their full forms

A contraction is the shortened form of a common phrase. “Isn’t” is the contraction of “is not”, and there may be some performance benefits to be gained by expanding such contractions. However, this is sligthly trickier than the previous few steps as no pre-defined regular expression exists for this purpose.

One solution to this is creating our own dictionary with the keys-value pairs representing the contracted and expanded forms, respectively, of phrases. Here’s a short example

textVariable = 'Sean isn\'t in the barn; we\'ve checked it already'

contractions = {"isn't":"is not", "we've":"we have"}

textVariable = textVariable.replace("’","'")

words = textVariable.split()

reformed = [contractions[word] if word in contractions else word for word in words]

textVariable = " ".join(reformed)

Printing this out shows us:

textVariable

'Sean is not in the barn; we have checked it already'

We’ve quickly seen some of the more common substeps within pre-processing of text data and how to execute them. Next, we will explore the what, how and why of feature representation of text data

Vectorisation & Feature Representation

Once our data is cleaned and processed, we can start to think about how to turn text into machine-readable inputs. That is the essence of feature representation. It is the method by which we map words to numbers, but in a way that allows the words to retain some inherent ‘meaning’ that is conducive to useful analysis. It will not be very useful, for example, to assign the word ‘bad’ the number ‘1’, the word ‘blue’ the number ‘2’ because there isn’t anything about those numbers that uniquely links them to those specific words. In other words, we don’t have a better justification for linking ‘1’ to ‘bad’ then we do for linking ‘1’ to ‘blue’ instead.

Luckily, there are several methods available to us that do link words and numbers in a meaningful way:

- Bag of Words (BOW)

- Term Frequency Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF)

- Word Embeddings

- Embeddings from Language Models (ELMo)

Let’s examine each method in turn

1) Bag of Words (BOW) using Scikit Learn

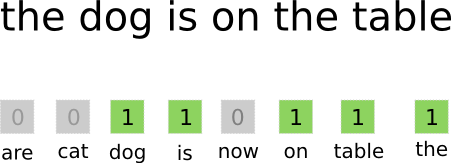

The simplest approach to turn words into numbers, the BOW method is best explained using a short example. Suppose our data set has 3 reviews and 100 total unique words. For the first review, BOW will create a 100 column by 1 row vector, as the number of columns is equal to the number of unique words. For each word that occurs both in this latter list and the single review, BOW assigns a value of ‘1’. For each word that does not overlap, a value of ‘0’ is assigned. This process is repeated for the 2nd and 3rd reviews

How does this help us? The intuition is that documents are similar if they have similar content. Further, that from the content alone we can learn something about the meaning of the document. And the gauge of similarity we are using here is the word overlap. So, if the first two reviews contain the word ‘great’ and are labelled as having a ‘positive sentiment’, our algorithms may ‘learn’ that ‘great’ is associated with a positive sentiment.

Let’s split our data into training and test sets, run the pre-processing from the previous post and use scikit learn’s CountVectorizer() to create a BOW for our Amazon product data

import numpy as np

import random

import pandas as pd

#Pre-processing related

import nltk

import spacy

nltk.download('wordnet')

import re

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

import textblob, string

from sklearn import model_selection

[nltk_data] Downloading package wordnet to

[nltk_data] /Users/alitaimurshabbir/nltk_data...

[nltk_data] Package wordnet is already up-to-date!

#from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

#data = pd.read_json('/Users/alitaimurshabbir/Desktop/Personal/GitHub/Sentiment NLP & Analysis/reviews_Video_Games_5.json', lines=True)

#data.drop(['asin','unixReviewTime', 'reviewTime'], axis = 1, inplace = True) #drop unnecessary columns

#data.head(2) #preview data

#quick pre-processing

def clean(text):

text = "".join([char for char in text if char not in string.punctuation]) #remove punctuations

text = ' '.join(re.sub("[\.\,\!\?\:\;\-\=]", " ", text).split()) #remove punctuations again

text = re.sub('[0-9]+', '', text) #remove numbers

text = ' '.join(re.sub( "(@[A-Za-z0-9]+)|(#[A-Za-z0-9]+)", ' ', text ).split()) #remove hashtags and mentions

text = ' '.join(re.sub("(\w+:\/\/\S+)", " ", text).split()) #remove URLs

text = text.lower() #lower-case the text

text = ' '.join([lemmatizer.lemmatize(word) for word in text.split()]) #lemmatising

return text

data['reviewText'] = data['reviewText'].apply(lambda x: clean(x))

X_train, X_val, y_train, y_val = model_selection.train_test_split(data['reviewText'], data['overall'], test_size = 0.3, shuffle = True, random_state = 42)

print(X_train[0])

print(y_train[0])

installing the game wa a struggle because of game for window live bugssome championship race and car can only be unlocked by buying them a an addon to the game i paid nearly dollar when the game wa new i dont like the idea that i have to keep paying to keep playingi noticed no improvement in the physic or graphic compared to dirt i tossed it in the garbage and vowed never to buy another codemasters game im really tired of arcade style rallyracing game anywayill continue to get my fix from richard burn rally and you should to httpwwwamazoncomrichardburnsrallypcdpbcrefsrieutfqidsrkeywordsrichardburnsrallythank you for reading my review if you enjoyed it be sure to rate it a helpful

1

Below, you can see a single review and the number count of unique words it contains

print(X_train[2])

print(X_train_count[2].sum())

st shipment received a book instead of the gamend shipment got a fake one game arrived with a wrong key inside on sealed box i got in contact with codemasters and send them picture of the dvd and the content they said nothing they can do it a fake dvdreturned it good bye

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-22-b8003fc81e5e> in <module>

1 print(X_train[2])

----> 2 print(X_train_count[2].sum())

NameError: name 'X_train_count' is not defined

One major downside of a BOW matrix is that it creates sparse vectors which makes computations resource-intensive, particularly with large datasets. It is also a very simplistic way of feature extraction. We will compare how well this method of feature representation does in terms of model performance later. Let’s set this aside for now and move onto the next method.

2) Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) using Scikit Learn

TF-IDF is a very useful ‘upgrade’ applied to the BOW method. Here’s how MonkeyLearn describes it:

“TF-IDF (term frequency-inverse document frequency) is a statistical measure that evaluates how relevant a word is to a document in a collection of documents. This is done by multiplying two metrics: how many times a word appears in a document, and the inverse document frequency of the word across a set of documents.”

So, if a word occurs frequently in a single review, but rarely in the whole corpus of text of all reviews, then it’s likely that that word is pretty relevant to that single review. TF-IDF allows us to capture this connection and gives more weight to such words. There is a specific mathematical formula used to calculate it, but we won’t cover that here.

Another interesting thing to note is that we can apply the TF-IDF method to phrases or n-grams; we are not just confined to single words. This means we can compare how often a phrase occurs in a single review and compare that to how often it occurs in the whole body of text. This may help us in sentiment analysis because phrases might be more conducive to capturing sentiment than single words.

Therefore, we will execute both word- and phrase-level TF-IDF vectorisation

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer #import TF-IDF Vectoriser

#tf-idf word-level vectorisation

TFIDF_vectoriser = TfidfVectorizer(analyzer='word', token_pattern=r'\w{1,}', max_features=5000)

TFIDF_vectoriser.fit(data['reviewText']) #fit the vectoriser onto our vocabulary

#transform our text data and store them within variables

X_train_tfidf = TFIDF_vectoriser.transform(X_train)

X_val_tfidf = TFIDF_vectoriser.transform(X_val)

#tf-idf n-gram level vectorisation. We define a phrase to be 3-words long

TFIDF_vect_ngram = TfidfVectorizer(analyzer='word', token_pattern=r'\w{1,}', ngram_range=(3,3), max_features=5000)

TFIDF_vect_ngram.fit(data['reviewText']) #fit the vectoriser onto our vocabulary

#transform X_train and X_val and store in separate variables

X_train_tfidf_ngram = TFIDF_vect_ngram.transform(X_train)

X_val_tfidf_ngram = TFIDF_vect_ngram.transform(X_val)

As before, we set these features aside for now and move onto the next feature representation method

3) Word Embeddings (Word2Vec & GloVe)

This is where things start to get really interesting. Rather than basic counts of what words/phrases appear in a single review vs all reviews, we are able to capture some actual semantic and mathematical association between words using word embeddings.

Let’s reiterate some important points before explaining word embeddings.

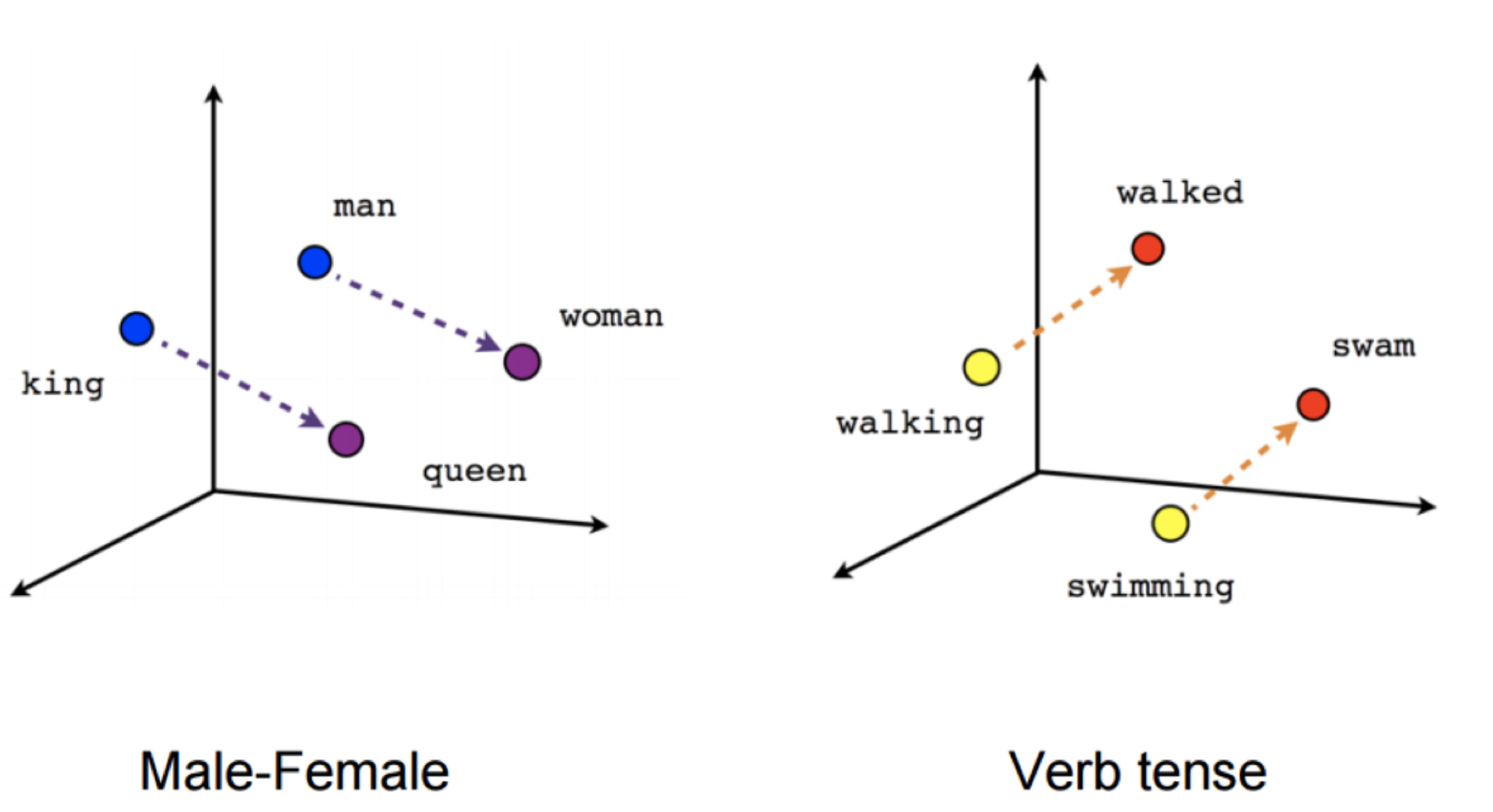

As described before, word vectors are numerical representations of words. Each vector (for a given word) can be thought of as a row with real numbers. With simpler approaches like BOW, we have seen that these vectors have binary values (1s and 0s).

With Word Embeddings and more advanced methods, these vectors have real number values. Using this method, we can map words in the vector space and use mathematical operations to get to other words. Similar words are clustered closer together while different words are further apart. The classic example here is: king - man + woman = queen. We can actually get to queen because of the way these words are mapped numerically in the vector space.

In the image below, on the left, all 4 words have been mapped to a vector space. If we subtract the ‘man’ vector from the ‘king’ vector and add the ‘woman’ vector, we will get to the ‘queen’ vector.

How is this possible? How can we come up with vectors that capture, among other things, that ‘king’ and ‘man’ (let us call this pair ‘A’) are similar, ‘woman’ and ‘queen’ are similar (‘B’) but ‘A’ and ‘B’ are different?

Well, it has to idea with the basic idea of distributional semantics which can be summed up in the so-called distributional hypothesis: linguistic items with similar distributions have similar meanings. The meaning of a word is given by the words that frequently appear close to it.

In other words, “you shall know a word by the company (context) it keeps” - J.R. Firth

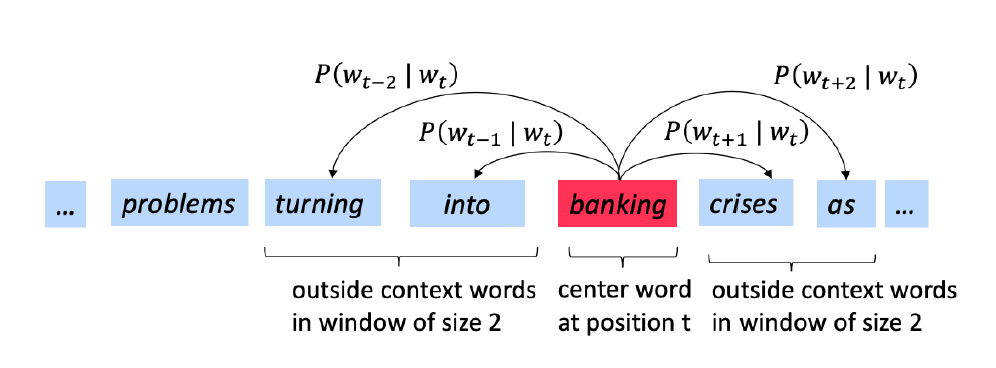

Let’s look at a specific model called Word2Vec for better understanding. Word2Vec is actually a 2-layer shallow neural network. This means it has only 1 hidden layer. Using the image below as a visual guide, we can explain how Word2Vec functions

- Represent each word in a sentence as a fixed vector

- Let one word, the first one, be your ‘centre’ c and identify the context or outer words o

- Repeat this process by iterating through the text and making each word the centre word

- Find the probability of c given o or vice versa, as stated by the conditional probability expressions in the image

- Adjust size of context window and repeat steps 1 through 4

- Adjust resulting vectors to maximise probability in step 4

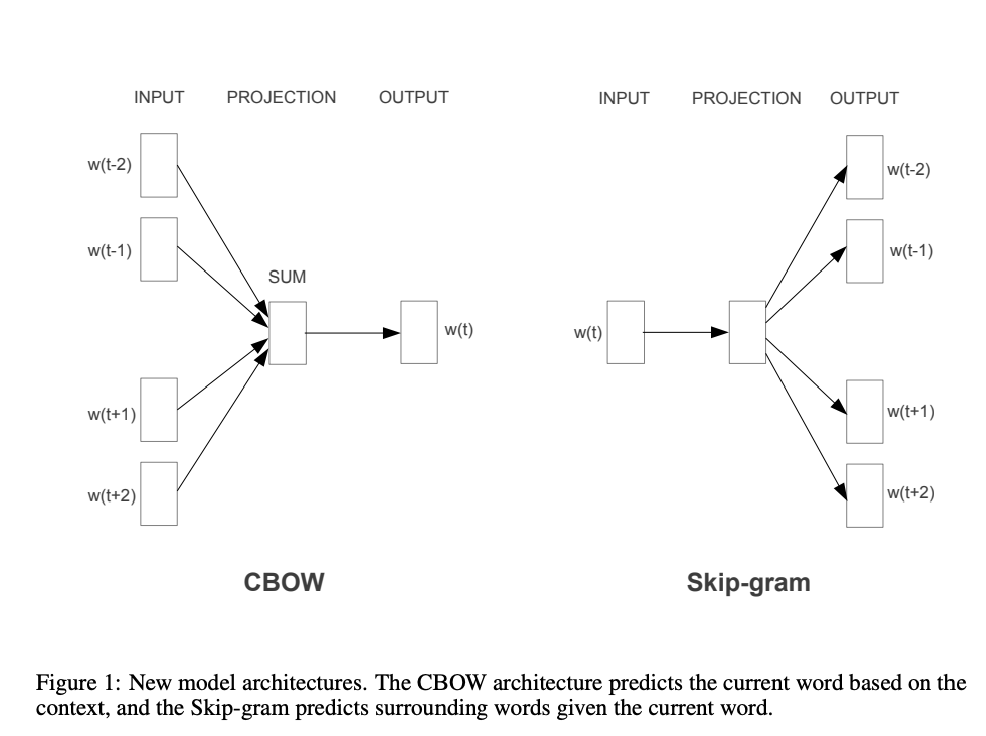

Word2Vec actually comes in 2 flavours, Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) and Skip-grams. Here is a very condensed explanation of how they differ and the contexts in which they are more suitable to be used:

In CBOW, we predict c from a bag of context words. CBOW is several times faster than skip-grams and provides a better frequency for frequent words

In skip-grams, we predict the position of outside words independent of position, given c. Skip-grams needs a small amount of training data and represents even rare words or phrases

An alternative to Word2Vec in creating word embeddings is Global Vectors for Word Representation or GloVe. It is a weighted least squares model that trains on global word-word co-occurrence counts, as opposed to Word2Vec which focuses on a local sliding window around each word to generate vectors.

The mechanism behind how GloVe works is pretty technical, and since I want to keep this post focused on a mix between explanation and implementation, I’ll refer you to this excellent article by Thushan Ganegedara on Medium for a more detailed explanation

One advantage of GloVe is that we have access to pre-trained word vectors available, trained on various corpora (bodies of text). This can become exceedingly handy depending on how unique our text domain is. For instance, people write on Twitter in a very unique style. If we had text data from Twitter that we wanted to analyse, then using Twitter-trained word vectors may result in better model performance.

For more general domains, we can always use more general word vectors. Wikipedia-trained word vectors could be a good approximation to use for general tasks. That’s what we will do now.

To begin, we need access to a txt file containing these embeddings. The file I use contains 300-dimensional word vectors trained on 6 billion tokens

globe_path = "/Users/alitaimurshabbir/Desktop/Personal/DataScience/GitHub/Sentiment NLP & Analysis/glove.6B.300d.txt" #set path

#load GloVe word embeddings

def load_word_embeddings(file=globe_path):

embeddings={}

with open(file,'r') as infile:

for line in infile:

values=line.split()

embeddings[values[0]]=np.asarray(values[1:],dtype='float32')

return embeddings

embeddings = load_word_embeddings()

Before we can actually create word embeddings using our reviewText series, we need to create a tokeniser function and define our stopwords

#create tokeniser function using spaCy

my_tok = spacy.load('en')

def spacy_tok(x):

return [token.text for token in my_tok.tokenizer(x)]

#get stopwords from nltk

nltk.download('stopwords')

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

stops=set(stopwords.words('english'))

#get non-stopwords from reviewText

def non_stopwords(reviews):

return {x:1 for x in spacy_tok(str(reviews).lower()) if x not in stops}.keys()

[nltk_data] Downloading package stopwords to

[nltk_data] /Users/alitaimurshabbir/nltk_data...

[nltk_data] Package stopwords is already up-to-date!

#create word embeddings using GloVe

def sentence_features_v2(s, embeddings=embeddings,emb_size=300):

# ignore stop words

words=non_stopwords(s)

words=[w for w in words if w.isalpha() and w in embeddings]

if len(words)==0:

return np.hstack([np.zeros(emb_size)])

M=np.array([embeddings[w] for w in words])

return M.mean(axis=0)

#create new sentence vectors

X_train_glove = np.array([sentence_features_v2(x) for x in X_train])

X_val_glove = np.array([sentence_features_v2(x) for x in X_val])

#let's quickly check the shape of one word vector. As expected, it is 300-dimensional

w = sentence_features_v2(X_train[0])

w.shape

(300,)

That’s it! We have gone through some of the more popular feature representation methods for text. The next steps are similar to those in a general classification task: train, validate and evaluate models.