Python End-to-End Machine Learning Project: Spotify Artist Success (Python)

1) Problem motivation and understanding

Over the last few years, the music industry has been dominated by digital streaming services, which produce vast amounts of data on listeners and their preferences. This has required major players in the industry to adopt a data driven approach to content delivery in order to stay competitive. Warner Music Group is looking to leverage its rich database to better understand the factors that have the most significant impact on the success of a new artist. This will allow them to optimise the allocation of resources when signing and promoting new artists.

For this case study, I used a Spotify dataset to predict the success of artists. In particular, I wanted to understand the role of Spotify playlists on the performance of artists. This is informed by Warner Music Group’s findings that certain playlists have more of an influence on the popularity, stream count and future success of an artist than others.

The hypothesis is that if Warner Music Group can predict which artists would appear on certain playlists that greatly influence popularity, stream count and future success of an artist before they actually appear on such playlists, they would be in an advantageous competitive position by signing such artists before Warner Music Group’s competitors do

Important

This project uses 3 different data files. 2 of these are available in the repository. The last one (‘cleaned_data.csv’) is too large to be uploaded to Github, and can be found here instead: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1nW2UlZqLxN5dHhMPldJnoJ-C3rgXvfv1

1.1) Approach and Insights

This project is framed as a supervised learning, classification task. The dependent variable is binary and showcases whether or not an artists appears on one or more key playlists. The independent variables and features include age of streamers, geography of streamers, source of streamers, stream count and so on

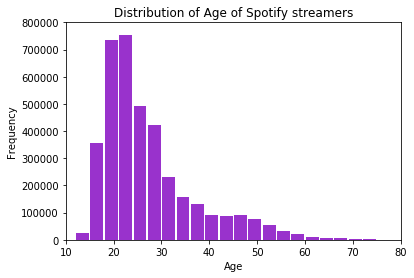

For visualisation, I created a multitude of graphs to get a better feel of the data. These graphs were mostly categorical in essence, as this was the nature of the pre-engineered dataset. I found, among other insights, the slight skew in terms of age for customers and the interesting omission of the most played playlists from the 4 target playlists. There was also a seasonal and weekly component to what songs/genres, and by extension what artists, were popular.

The majority of the analysis related to feature engineering, since the raw data and features were not suited to ML algorithms. Features were divided into Artist, Playlist and User levels. In the first category, I created a measure of how passionate an artist’s fans were through the measure of repeated streams, called ‘Passion Score’. A similar feature was created for the second category. For the final category, I built a gender and age level audience profile per artist, to see if demographics had any major effect on predicting success.

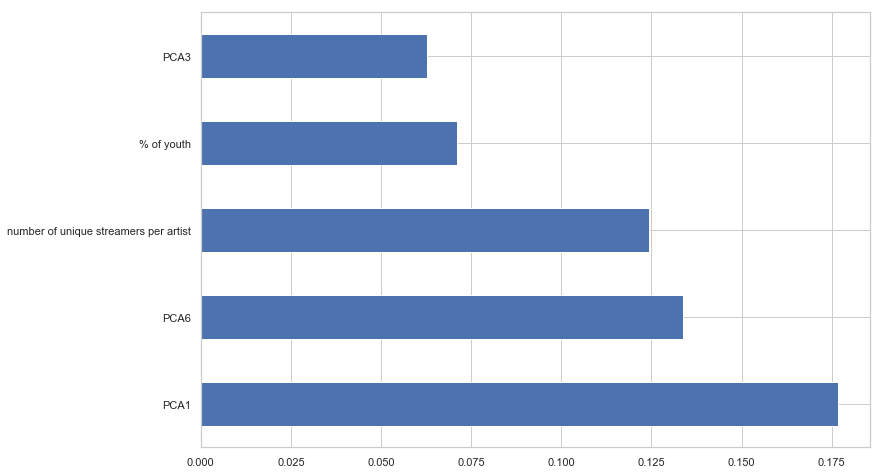

Next I prepared the data to be fed into an algorithm. Key tasks completed here included splitting the data, checking for correlations, executing PCA, filling missing values wand dealing with class balance. PCA was executed on region codes to incorporate a geographical aspect into predicting success and to extract the most important data from 600+ region codes. The first such principal component turned out to be the most powerful predictive feature.

Additionally, class balance initially proved to be an issue, since there were many more unsuccessful cases than successful ones in our data, especially after the training-test split. To overcome this, I oversampled the successful cases (in only training set) and included the necessary caveats that this oversampling entailed.

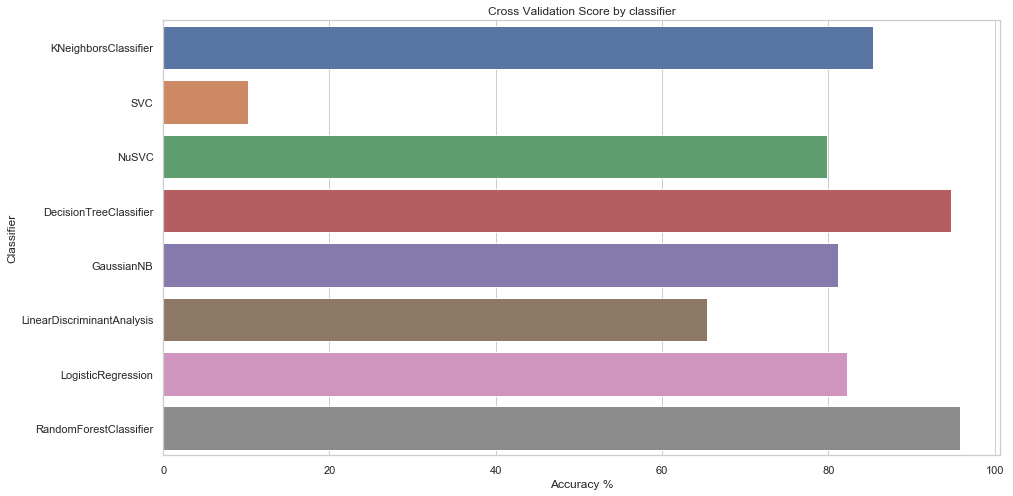

A search for the best-performing model followed, followed by extensive evaluation. Decision Trees and Random Forests were found to be the best performing in terms of cross-validation scores. I choose the latter in tuning hyperparameters via grid search, and ended with a cross-validation score of 97%. Further attempts to using ensemble methods with my model (which by itself, of course, is an ensemble method) with AdaBoost yielded large decreases in performance, so such methods were not considered going forward

1.2) Results

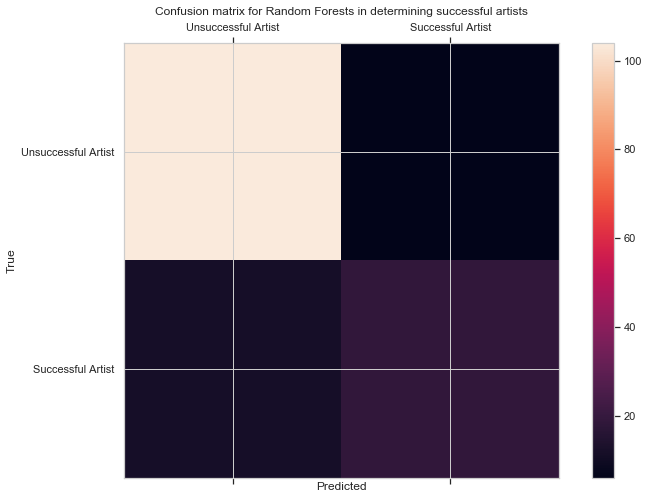

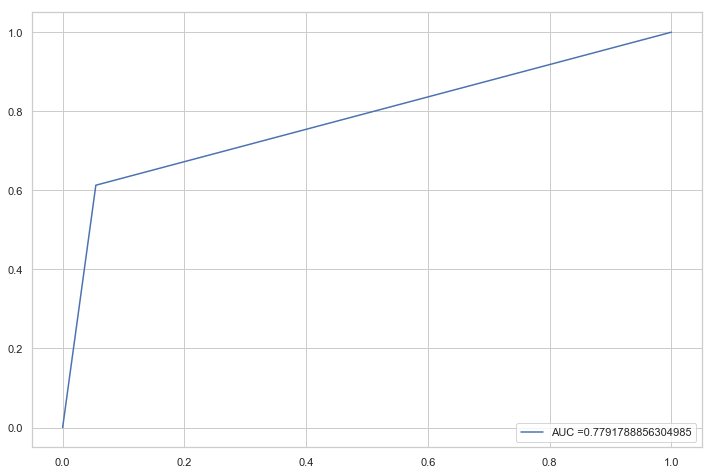

Testing my model on the hold-out set resulted in an accuracy of 87%, which is good but not great, as it can still lead to WarnerMusic missing out on potentially successful artists. I believe the reason why the model cannot break the 90% barrier is the very small hold-out set size, with even fewer successful cases. My Confusion Matrix seems to confirm this. Oversampling was not executed on this hold-out set. Using ROC, the area under the curve is 78%, while the most important features are geographical (first principal component), number of unique streamers per artist and % of youth streamers. Thus, if an artist is popular among a multitude of young streamers, they are more likely to be successful.

1.3) How to run this project

- Download the Jupyter notebook

- Download the data files named cleaned_data.csv, newartists2015onwards.csv and playlists_ids_and_titles.csv\

- Ensure you import all the required modules. The code for this is already present in the Notebook but a full list of the imports can be found in the requirements.txt file

- Change paths to load the data from your local machine once you have downloaded the data files mentioned in point 2

- Run the whole Jupyter Notebook

1.4) Problem Exposition

1.41) Streaming Music

When artists release music digitally, details of how their music is streamed can be closely monitored.

Some of these details include:

- How listeners found their music (a recommendation, a playlist)

- Where and when (a routine visit to the gym, a party, while working).

- On what device (mobile / PC)

- And so on…

Spotify alone process nearly 1 billion streams every day (Dredge, 2015) and this streaming data is documented in detail every time a user accesses the platform.

Analyzing this data potentially enables me to gain a much deeper insight into customers’ listening behavior and individual tastes.

Spotify uses it to drive their recommender systems – these tailor and individualize content as well as helping the artists reach wider and more relevant audiences.

Warner Music would like to use it to better understand the factors that influence the future success of its artists, identify potentially successful acts early on in their careers and use this analysis to make resource decisions about how they market and support their artists.

1.42) What are Spotify Playlists and why are relevant today?

A playlist is a group of tracks that you can save under a name, listen to, and update at your leisure.

Figure 1. Screen shot of Spotify product show artists and playlists.

Spotify currently has more than two billion publicly available playlists, many of which are curated by Spotify’s in-house team of editors.

The editors scour the web on a daily basis to remain up-to-date with the newest releases, and to create playlists geared towards different desires and needs.

Additionally, there are playlists such as Discover Weekly and Release Radar that use self-learning algorithms to study a user’s listening behavior over time and recommend songs tailored to his/her tastes.

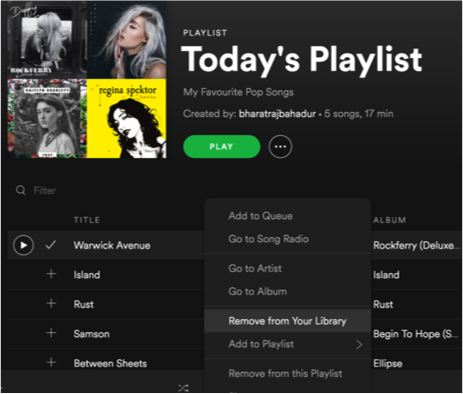

The figure below illustrates the progression of artists on Spotify Playlists:

Figure 2. Figure to illustrate selecting artists and building audience profiles over progressively larger audiences of different playlists.

The artist pool starts off very dense at the bottom, as new artists are picked up on the smaller playlists, and thins on the way to the top, as only the most promising of them make it through to more selective playlists. The playlists on the very top contain the most successful, chart-topping artists.

An important discovery that has been made is that certain playlists have more of an influence on the popularity, stream count and future success of an artist than others

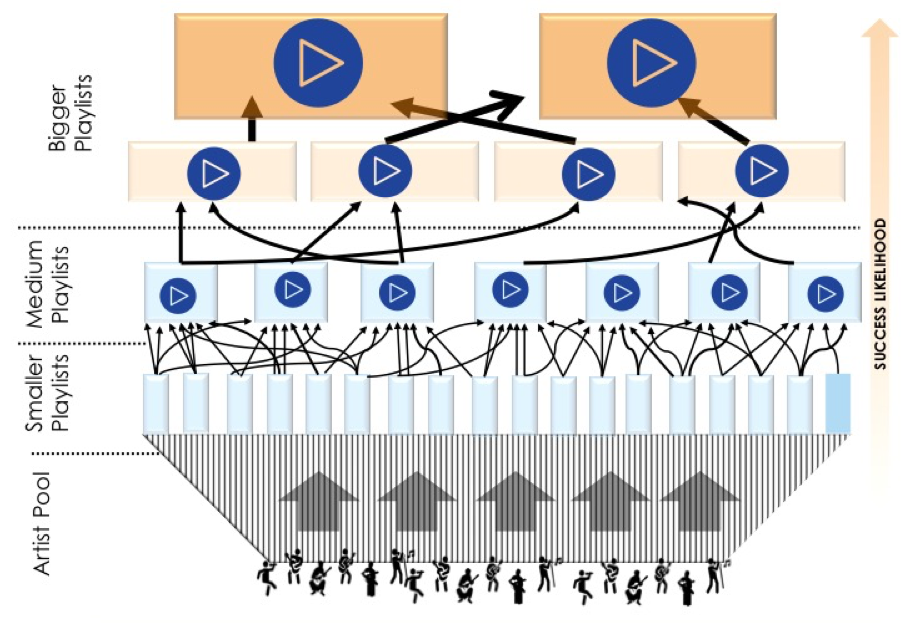

Figure 3. Figure to illustrate taking song stream data and using it to predict the trajectory, and likely success, of Warner artists.

Moreover, some playlists have been seen to be pivotal in the careers of successful artists. Artists that do make it onto one of these key playlists frequently go on to become highly ranked in the music charts.

It is the objective of Warner’s A&R team to identify and sign artists before they achieve this level of success i.e. before they get selected for these playlists, in order to increase their ROI.

In other words, we want to find the artists most likely to make it to one of these ‘big playlists’

In ML terms, this means creating a predicitve model to assess which artists will most likely end up on one of these playlists. The 4 target playlists are outlined in following sections

1.43) Business Problem → Data Problem

Now that I have a better understanding of the business problem, I can begin to think about how we could model this problem using data.

The first thing I can do is defining a criterion for measuring artist success.

Based on our business problem, one way in which I can do this is to create a binary variable representing the success / failure of an artist and determined by whether a song ends up on a key playlist (1), or not (0). I can then generate features for that artist to determine the impact they have on the success of an artist.

My problem thus becomes a classification task, which can be modeled as follows:

Artist Feature 1 + Artist Feature 2 …. + Artist Feature N = Probability of Success

where,

Success (1) = Artist Features on Key Playlist

The key playlists I will use for this case study are the 4 listed below, as recommended by Warner Analysts:

- Hot Hits UK

- Massive Dance Hits

- The Indie List

- New Music Friday

The project task is to take a look at the Spotify dataset to see how I might be able to set up this classification model.

2. Preparing the problem

# Preamble

#import sherlockml.datasets as sfs

import pandas as pd

import random

#sfs.get('/input/spotfunc.py', 'spotfunc.py')

#sfs.get('/input/playlists_ids_and_titles.csv', 'playlists_ids_and_titles.csv')

#sfs.get('/input/newartists2015onwards.csv', 'newartists2015onwards.csv')

# Import all required libraries

import pandas as pd

from pandas import Series, DataFrame

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.mlab as mlab

from IPython.display import display, Markdown, Latex

figNo = 1

from pylab import *

import seaborn as sns

2.1) Data Understanding

A year’s worth of Spotify streaming data in the WMG database amounts to approximately 50 billion rows of data i.e. 50 billion streams (1.5 to 2 terabytes worth), with a total of seven years of data stored altogether (2010 till today).

For the purposes of this case study, I will be using a sample of this data. The dataset uploaded on the Sherlock server is about 16GB, containing data from 2015 - 2017. Given the limits on RAM and cores, I will be taking a further sample of this data for purposes of this case study: a 10% random sample of the total dataset, saved as ‘cleaned_data.csv’.

Note: The code for this sampling in included below, but commented out.

We can begin with reading in the datasets we will need. We will be using 2 files:

- Primary Spotify dataset

- Playlist Name Mapper (only playlist IDs provided in primary dataset)

# %%time

# Sampling data to read in 10%

# sfs.get('/input/all_artists_with_date_time_detail.csv', 'client-data.csv')

# # Read in data

# # The data to load

# f = 'client-data.csv'

# # Count the lines

# num_lines = sum(1 for l in open(f))

# n = 10

# # Count the lines or use an upper bound

# num_lines = sum(1 for l in open(f))

# # The row indices to skip - make sure 0 is not included to keep the header!

# skip_idx = [x for x in range(1, num_lines) if x % n != 0]

# # Read the data

# data = pd.read_csv(f, skiprows=skip_idx )

Read in the data

%%time

# Read in sampled data. Please change the path here to work with your local machine

data = pd.read_csv('PATH/TO/FILE/cleaned_data.csv')

print('rows:',len(data))

# Keep a copy of original data in case of changes made to dataframe

all_artists = data.copy()

# Load playlist data. As before, ensure you change the path accordingly

playlist_ids_and_titles = pd.read_csv('PATH/TO/FILE/playlists_ids_and_titles.csv',encoding = 'latin-1',error_bad_lines=False,warn_bad_lines=False)

# Keep only those with 22 characters (data cleaning)

playlist_mapper = playlist_ids_and_titles[playlist_ids_and_titles.id.str.len()==22].drop_duplicates(['id'])

rows: 3805499

CPU times: user 30.1 s, sys: 5.68 s, total: 35.8 s

Wall time: 34.6 s

data.head(2)

| Unnamed: 0 | Unnamed: 0.1 | Unnamed: 0.1.1 | day | log_time | mobile | track_id | isrc | upc | artist_name | ... | hour | minute | week | month | year | date | weekday | weekday_name | playlist_id | playlist_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 9 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 9) | 10 | 20160510T12:15:00 | True | 8f1924eab3804f308427c31d925c1b3f | USAT21600547 | 7.567991e+10 | Sturgill Simpson | ... | 12 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 2016 | 2016-05-10 | 1 | Tuesday | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | 1 | 19 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 19) | 10 | 20160510T12:15:00 | True | 8f1924eab3804f308427c31d925c1b3f | USAT21600547 | 7.567991e+10 | Sturgill Simpson | ... | 12 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 2016 | 2016-05-10 | 1 | Tuesday | NaN | NaN |

2 rows × 45 columns

# find the data types of features

data.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 3805499 entries, 0 to 3805498

Data columns (total 45 columns):

Unnamed: 0 int64

Unnamed: 0.1 int64

Unnamed: 0.1.1 object

day int64

log_time object

mobile bool

track_id object

isrc object

upc float64

artist_name object

track_name object

album_name object

customer_id object

postal_code object

access object

country_code object

gender object

birth_year float64

filename object

region_code object

referral_code float64

partner_name object

financial_product object

user_product_type object

offline_timestamp float64

stream_length float64

stream_cached float64

stream_source object

stream_source_uri object

stream_device object

stream_os object

track_uri object

track_artists object

source float64

DateTime object

hour int64

minute int64

week int64

month int64

year int64

date object

weekday int64

weekday_name object

playlist_id object

playlist_name object

dtypes: bool(1), float64(7), int64(9), object(28)

memory usage: 1.3+ GB

# It is also useful to get a numerical summary

data.describe()

| Unnamed: 0 | Unnamed: 0.1 | day | upc | birth_year | referral_code | offline_timestamp | stream_length | stream_cached | source | hour | minute | week | month | year | weekday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 | 3805499.0 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.795478e+06 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.805499e+06 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 | 3.805499e+06 |

| mean | 1.902749e+06 | 1.902750e+07 | 10.0 | 2.389062e+11 | 1.990107e+03 | NaN | NaN | 1.891587e+02 | NaN | NaN | 1.373665e+01 | 2.254671e+01 | 2.316008e+01 | 5.970407e+00 | 2.016437e+03 | 2.837800e+00 |

| std | 1.098553e+06 | 1.098553e+07 | 0.0 | 2.757391e+11 | 1.068282e+01 | NaN | NaN | 6.105546e+01 | NaN | NaN | 5.400456e+00 | 1.675157e+01 | 1.320996e+01 | 3.036840e+00 | 5.964080e-01 | 2.001057e+00 |

| min | 0.000000e+00 | 9.000000e+00 | 10.0 | 1.686134e+10 | 1.867000e+03 | NaN | NaN | 3.000000e+01 | NaN | NaN | 0.000000e+00 | 0.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 1.000000e+00 | 2.014000e+03 | 0.000000e+00 |

| 25% | 9.513745e+05 | 9.513754e+06 | 10.0 | 7.567991e+10 | 1.987000e+03 | NaN | NaN | 1.720000e+02 | NaN | NaN | 1.000000e+01 | 1.500000e+01 | 1.400000e+01 | 4.000000e+00 | 2.016000e+03 | 1.000000e+00 |

| 50% | 1.902749e+06 | 1.902750e+07 | 10.0 | 1.902958e+11 | 1.993000e+03 | NaN | NaN | 2.000000e+02 | NaN | NaN | 1.400000e+01 | 3.000000e+01 | 2.300000e+01 | 6.000000e+00 | 2.016000e+03 | 3.000000e+00 |

| 75% | 2.854124e+06 | 2.854124e+07 | 10.0 | 1.902960e+11 | 1.997000e+03 | NaN | NaN | 2.240000e+02 | NaN | NaN | 1.800000e+01 | 4.500000e+01 | 3.200000e+01 | 8.000000e+00 | 2.017000e+03 | 5.000000e+00 |

| max | 3.805498e+06 | 3.805499e+07 | 10.0 | 5.414940e+12 | 2.017000e+03 | NaN | NaN | 9.000000e+02 | NaN | NaN | 2.300000e+01 | 4.500000e+01 | 5.000000e+01 | 1.200000e+01 | 2.017000e+03 | 6.000000e+00 |

An additional idea is to check for missing values

data.isnull().sum()

Unnamed: 0 0

Unnamed: 0.1 0

Unnamed: 0.1.1 0

day 0

log_time 0

mobile 0

track_id 0

isrc 4

upc 0

artist_name 0

track_name 0

album_name 0

customer_id 0

postal_code 1352181

access 0

country_code 0

gender 40422

birth_year 10021

filename 0

region_code 261956

referral_code 3805499

partner_name 3378646

financial_product 2329099

user_product_type 22992

offline_timestamp 3805499

stream_length 0

stream_cached 3805499

stream_source 0

stream_source_uri 2761628

stream_device 0

stream_os 0

track_uri 0

track_artists 0

source 3805499

DateTime 0

hour 0

minute 0

week 0

month 0

year 0

date 0

weekday 0

weekday_name 0

playlist_id 2761628

playlist_name 2826389

dtype: int64

This analysis shows that I am missing entries for postal code in a great number of cases, and for nearly all cases of the Stream Source URI. I may need to deal with this later

Each row in the data is a unique stream – every time a user streams a song in the Warner Music catalogue for at least 30 seconds it becomes a row in the database. Each stream counts as a ‘transaction’, the value of which is £0.0012, and accordingly, 1000 streams of a song count as a ‘sale’ (worth £1) for the artist. The dataset is comprised of listeners in Great Britain only.

Not all the columns provided are relevant to me. Lets take a look at some basic properties of the dataset, and identify the columns that are important for this study

The columns I should focus on for this case study are:

- Log Time – timestamp of each stream

- Artist Name(s) – some songs feature more than one artist

- Track Name

- ISRC - (Unique code identifier for that version of the song, i.e. radio edit, album version, remix etc.)

- Customer ID

- Birth Year

- Location of Customer

- Gender of Customer

- Stream Source URI – where on Spotify was the song played – unique playlist ID, an artist’s page, an album etc.

2.2) Exploratory Analysis and Plots

Now I will look at the data set in more detail.

I am going to visualise and explore the following set of variables:*

- Age

- Gender

- Streams by month and weekday

- Most popular playlists

Age

-

create an ‘Age’ variable to make it easier to interpret*

-

drop missing values for ‘Age’

-

visualise the distribution of ‘Age’

data['birth_year'] = 2017 - data['birth_year']

data.rename(columns = {'birth_year':'age'}, inplace = True)

data['age']= data['age'].dropna()

data['age'].dropna(inplace = True)

data['age'].isna().sum()

0

data['age'].describe()

count 3.795478e+06

mean 2.689286e+01

std 1.068282e+01

min 0.000000e+00

25% 2.000000e+01

50% 2.400000e+01

75% 3.000000e+01

max 1.500000e+02

Name: age, dtype: float64

#I restrict the x-axis range to an upper limit of 80, instead of the max age of 150 because the frequency of ages past 80 is minimal and

#restriction gives us a much clearer view of distribution

plt.hist(data['age'], bins = 50,color = 'darkorchid', rwidth = 0.9)

plt.xlabel('Age')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Distribution of Age of Spotify streamers')

plt.axis([10, 80, 0, 800000])

plt.grid(False)

As expected, Spotify’s customers are heavily skewed towards younger individuals

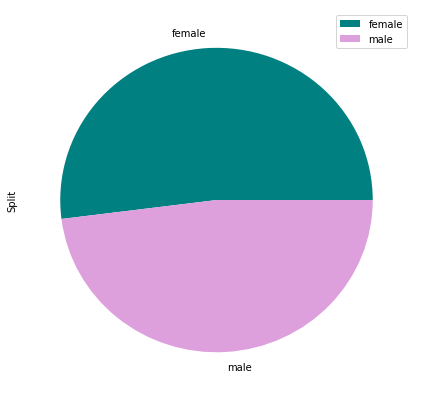

Gender

#get number of unique male and female streamers

unique_genders = data[['customer_id', 'gender']]

unique_genders = unique_genders.groupby('gender').nunique()

unique_genders = unique_genders.drop('gender', axis=1)

unique_genders = unique_genders.rename(columns = {'customer_id':'Split'})

unique_genders

| Split | |

|---|---|

| gender | |

| female | 1076907 |

| male | 994741 |

unique_genders.plot(kind='pie', subplots=True, colors = ['teal', 'plum'], figsize=(7, 7))

# females slightly outnumber males, but not to the extent of introducing an imbalance

array([<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1c296290>],

dtype=object)

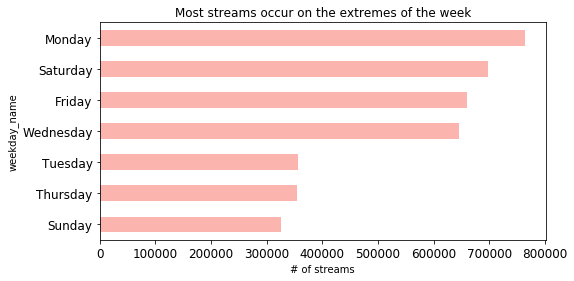

Stream frequency by weekday and month

# streams by weekday

streams_by_day = data.groupby('weekday_name').count()

streams_by_day['Weekday'] = streams_by_day.index

streams_by_day = streams_by_day.sort_values('day')

streams_by_day_plot = streams_by_day[['Weekday', 'day']].plot(kind='barh', color= plt.cm.Pastel1(np.arange(len(streams_by_day))), title = 'Most streams occur on the extremes of the week', figsize = (8, 4), legend = False, fontsize = 12)

streams_by_day_plot.set_xlabel('# of streams')

Text(0.5,0,'# of streams')

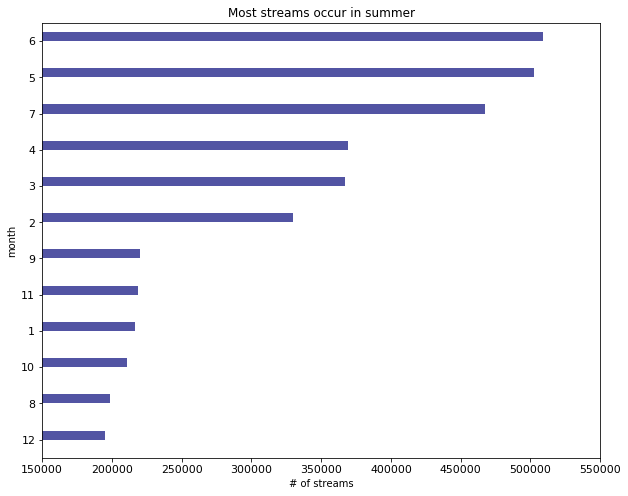

# streams by month

streams_by_month = data.groupby('month').count()

streams_by_month['Month'] = streams_by_month.index

streams_by_month = streams_by_month.sort_values('year')

streams_by_month_plot = streams_by_month[['Month', 'day']].plot(kind='barh', color= plt.cm.tab20b(np.arange(len(streams_by_day))), title = 'Most streams occur in summer', figsize = (10, 8), legend = False, fontsize = 11)

streams_by_month_plot .set_xlim((150000, 550000))

streams_by_month_plot.set_xlabel("# of streams")

Text(0.5,0,'# of streams')

The motivation behind these plots is as follows. It is likely that, as a whole, certain kinds of songs are more popular in certain parts of the year, and this may factor into whether or not an artist is successful. This is because artists release songs pertaining only to 2 or 3 genres normally.

For example, it is usually the case that songs beloning to the 'dance', 'pop', 'electronic' and 'party' genres are played much more during the summer than they are in winter. Similarly, Christmas songs will be played more often in the winter months

My visualisation shows us that, by far, most songs are indeed streamed in the summer, and at the end (leisure time) and beginning of the week. On Mondays, it is possible that a significant portion of streams is related to users exercising at a gym, as people tend to exercise on a Monday to have a 'positive start' to the week. Again, certain kinds of songs may be more popular when it comes to physical activity.

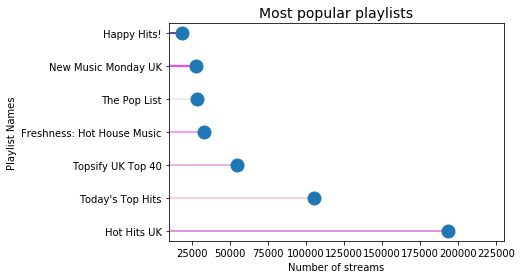

Most popular playlists

playlist_data = DataFrame(data['playlist_name'].value_counts())

playlist_data = playlist_data.drop(playlist_data.index[7:] )

playlist_data = playlist_data.rename(columns = {'playlist_name':'Number of streams'})

# create lollipop plot

my_range=range(1,len(playlist_data.index)+1)

import seaborn as sns

Colours = ['orchid','pink','plum','violet',

'lavender','fuchsia','indigo']

plt.hlines(y=my_range, xmin=0, xmax=playlist_data['Number of streams'], color=Colours)

plt.plot(playlist_data['Number of streams'], my_range, "o", markersize = 13)

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = [12,8]

plt.yticks(my_range, playlist_data.index)

plt.title("Most popular playlists", loc='center', size = 14)

plt.xlabel('Number of streams')

plt.ylabel('Playlist Names')

plt.xlim(left = 10000, right = 230000)

(10000, 230000)

Interestingly, of the 4 key playlists outlined by Warner analysts, only 1 (Hot Hits UK) is among the most popular playlists by number of streams.

We are unsure as to why said analysts recommended the paylists they did, but do believe that they had valid reasons for doing so.

This may point to the idea that number of streams per playlist, while an important factor, is not given a hugely significant amount of weight by Warner’s analysts. In turn, this may better inform our understanding of what features to include in the final model.

3. Data Preperation and Feature Engineering

From our business understanding, I know that our criteria for success is whether or not an artist has been on one of 4 key playlists. The column ‘stream_source_uri’, contains data about the source of the stream – whether it was from an artist’s page, an album, a playlist etc.

For streams coming from different playlists, only the Spotify URI code is provided. To make sense of this column and identify our key playlists, I can use the additional table provided that we cleaned above and named ‘playlist_mapper’.

We can being by out data preperation by subsetting the 4 key playlists we are interested in and creating our dependent variable:

Create Dependent Variable

Each source has a unique url. Since the stream source uri gives us a tonne of missing values, I am going to use the playlist_id name instead. The key playlists we will use for this case study are the 4 listed below, as recommended by Warner Analysts:

- Hot Hits UK

- Massive Dance Hits

- The Indie List

- New Music Friday

# select relevant playlists

target_playlists = ['Hot Hits UK', 'Massive Dance Hits', 'The Indie List', 'New Music Friday']

#return a filtered view of main dataframe 'data' where only target playlists are shown:

data.loc[data["playlist_name"].isin(target_playlists), ].head()

| Unnamed: 0 | Unnamed: 0.1 | Unnamed: 0.1.1 | day | log_time | mobile | track_id | isrc | upc | artist_name | ... | hour | minute | week | month | year | date | weekday | weekday_name | playlist_id | playlist_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 633 | 633 | 6339 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 6339) | 10 | 20160410T12:45:00 | False | db62b1d507bc4fd1bc8b4785d82d6356 | USAT21601204 | 7.567991e+10 | Vinyl on HBO | ... | 12 | 45 | 14 | 4 | 2016 | 2016-04-10 | 6 | Sunday | 6FfOZSAN3N6u7v81uS7mxZ | Hot Hits UK |

| 17270 | 17270 | 172709 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 172709) | 10 | 20160210T18:30:00 | False | bcdbf945cb194356b39ec0d36476e641 | AUUQU1600001 | 8.256463e+11 | Xavier Dunn | ... | 18 | 30 | 6 | 2 | 2016 | 2016-02-10 | 2 | Wednesday | 6FfOZSAN3N6u7v81uS7mxZ | Hot Hits UK |

| 26996 | 26996 | 269969 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 269969) | 10 | 20160710T10:00:00 | True | de3c49e047a945aba049b7467f9a20ad | USAT21601112 | 7.567991e+10 | Sir The Baptist | ... | 10 | 0 | 27 | 7 | 2016 | 2016-07-10 | 6 | Sunday | 6FfOZSAN3N6u7v81uS7mxZ | Hot Hits UK |

| 29244 | 29244 | 292449 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 292449) | 10 | 20160510T17:00:00 | False | 3ccdfba451974b848e509b3a97b553ba | FR9W11520485 | 1.902960e+11 | Amir | ... | 17 | 0 | 19 | 5 | 2016 | 2016-05-10 | 1 | Tuesday | 6FfOZSAN3N6u7v81uS7mxZ | Hot Hits UK |

| 60803 | 60803 | 608039 | ('small_artists_2016.csv', 608039) | 10 | 20160510T11:15:00 | False | 5e6ae0c4967047dbb832caec9b1df082 | FR43Y1600020 | 1.902960e+11 | Starlovers | ... | 11 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 2016 | 2016-05-10 | 1 | Tuesday | 6FfOZSAN3N6u7v81uS7mxZ | Hot Hits UK |

5 rows × 45 columns

# total number of successful and unsuccessful streams

data['Success'] = np.where(data.playlist_name.isin(target_playlists), 1, 0)

data['Success'].value_counts()

0 3602720

1 202779

Name: Success, dtype: int64

# number of unique successful artists

data.groupby('Success').artist_name.nunique()

Success

0 661

1 83

Name: artist_name, dtype: int64

Create binary dependent variable

successful = pd.DataFrame(data.groupby('artist_name').Success.sum())

depvar_df = pd.DataFrame(successful[successful['Success'] !=0])

successful['Successful Artist or Not'] = np.where(successful['Success'] > 0, 1, 0) # new variable where '0' means unsuccessful and '1' otherwise

successful

| Success | Successful Artist or Not | |

|---|---|---|

| artist_name | ||

| #90s Update | 0 | 0 |

| 17 Memphis | 0 | 0 |

| 2D | 0 | 0 |

| 3JS | 0 | 0 |

| 99 Percent | 0 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| birthday | 0 | 0 |

| dvsn | 11 | 1 |

| flor | 9 | 1 |

| gnash | 8961 | 1 |

| livetune+ | 0 | 0 |

661 rows × 2 columns

successful = successful.drop('Success', axis = 1)

successful

| Successful Artist or Not | |

|---|---|

| artist_name | |

| #90s Update | 0 |

| 17 Memphis | 0 |

| 2D | 0 |

| 3JS | 0 |

| 99 Percent | 0 |

| ... | ... |

| birthday | 0 |

| dvsn | 1 |

| flor | 1 |

| gnash | 1 |

| livetune+ | 0 |

661 rows × 1 columns

Now that I have created our dependent variable – whether an artist is successful or not, I can look at generating a set of features, based on the columns within our dataset, that I think might best explain the reasons for this success.

FEATURE ENGINEERING

There are a large number of factors that could have an impact on the success of an artist, such as:

- the influence of a playlist

- the popularity of an artist in a certain geographical region.

To build a predictive model for this problem, we first need to turn these (largely qualitative) factors into measurable quantities. Characteristics like ‘influence’ and ‘popularity’ need to be quantified and standardized for all artists, to allow for a fair comparison.

The accurateness of these numerical estimates will be the fundamental driver of success for any model I build. There are many approaches one might take to generate features. Based on the data columns available to me, a sensible approach is to divide our feature set into three groups:

- Artist Features

- Playlist Features

- User-base features

3.1) Artist features

- Stream count

- Total Number of users

- Passion Score

The metric passion score is a metric suggested to us by Warner business analysts.

It is defined as the number of stream divided by the total number of users.

Warner analysts believe that repeated listens by a user is a far more indicative future success that simply total number of listens or total unique users. By including this in my model, I can evaluate whether this metric in fact might be of any significance.

#Stream count per artist

streams_per_artist = data.artist_name.value_counts() #getting no. of observations per artist

streams_per_artist = DataFrame(streams_per_artist) #turning it into dataframe

streams_per_artist.reset_index(level = 0, inplace = True) #reset labels

streams_per_artist.columns = ['artist_name', 'streams_count_per_artist'] #add labels

# Number of users per artist

simple_dataframe = data[['artist_name','customer_id']] #create simple dataframe with two columns that I need

users_per_artist = simple_dataframe.groupby(['artist_name']).nunique() #get the unique number of customer_id per artist

users_per_artist = users_per_artist.drop('artist_name', axis = 1) #remove labels

#Passion score

#merge stream per artist and users per artist dataframes

passion_score_final = streams_per_artist.merge(users_per_artist, how = 'left', left_on = 'artist_name', right_index = True)

passion_score_final.head()

| artist_name | streams_count_per_artist | customer_id | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Charlie Puth | 447873 | 367023 |

| 1 | Dua Lipa | 315663 | 260778 |

| 2 | Lukas Graham | 311271 | 247580 |

| 3 | Cheat Codes | 255820 | 225658 |

| 4 | Anne-Marie | 247934 | 220413 |

#create new column for passion score

passion_score_final['passion_score_final'] = passion_score_final['streams_count_per_artist']/passion_score_final['customer_id']

artist_df = passion_score_final.copy()

artist_df = artist_df.rename(columns = {'customer_id':'streamers_per_artist'})

artist_df.set_index('artist_name', inplace = True) #replace index with artist_name

# Quantified artist features dataframe

artist_df

| streams_count_per_artist | streamers_per_artist | passion_score_final | |

|---|---|---|---|

| artist_name | |||

| Charlie Puth | 447873 | 367023 | 1.220286 |

| Dua Lipa | 315663 | 260778 | 1.210466 |

| Lukas Graham | 311271 | 247580 | 1.257254 |

| Cheat Codes | 255820 | 225658 | 1.133662 |

| Anne-Marie | 247934 | 220413 | 1.124861 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Arsen | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 |

| Helena Majdaniec | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 |

| Ugo | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 |

| Coraluna | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 |

| Deuspi | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 |

661 rows × 3 columns

3.2) Playlist Features

Understanding an artist’s growth as a function of his/her movement across different playlists is potentially key to understanding how to identify and breakout new artists on Spotify.

In turn, this could help me identify the most influential playlists and the reasons for their influence.

One way to model the effect of playlists on an artist’s performance has been to include them as categorical features in our model, to note if there are any particular playlists or combinations of playlists that are responsible for propelling an artist to future success:

Artist Feature 1 + Artist Feature 2 …. + Artist Feature N = Probability of Success

Success (1) = Artist Features on Key Playlist Failure (0) = Artist Not Featured on Key Playlist

Where,

⇒Artist Feature N = Prior Playlist 1 + Prior Playlist 2 +…Prior Playlist N

Given that I have over 19,000 playlists in our dataset or 600 artists, using the playlists each artist has featured on, as categorical variables would lead to too many features and a very large, sparse matrix.

Instead, I need to think of ways to summarize the impact of these playlists. One way to do this would be to consider the top 20 playlists each artist has featured on.

Even better would be to come up with one metric that captures the net effect of all top 20 prior playlists, for each artist, rather including using all 20 playlists for each artists as binary variables. The intuition here is that if this metric as a whole has an influence on the performance of an artist, it would suggest that rather than the individual playlists themselves, it is a combination of their generalized features that affects the future performance of an artist.

Accordingly, different combinations of playlists could equate to having the same impact on an artist, thereby allowing me to identify undervalued playlists.

Some of the features such a metric could use is the number of unique users or ‘reach’, number of stream counts, and the passion score of each playlist

- Prior Playlist Stream Counts

- Prior Playlist Unique Users (Reach)

- Prior Playlist Passion Score

There are several other such features that you could generate to better capture the general characteristics of playlists, such as the average lift in stream counts and users they generate for artists that have featured on them.

The code to calculate these metrics is provided below:

# obtain prior playlist stream counts

playlist_df = data[['playlist_name', 'artist_name', 'customer_id']]

playlist_df = playlist_df.dropna()

playlist_df_1 = playlist_df.dropna()

playlist_df_1 = DataFrame(playlist_df_1.groupby('artist_name').playlist_name.value_counts())

playlist_df_1 = playlist_df_1.rename(columns = {'playlist_name':'Prior Playlist Stream Counts'})

playlist_df_1

# obtain unique number of streamers per playlist

playlist_df_2 = DataFrame(playlist_df.groupby('playlist_name').customer_id.nunique())

playlist_df_2 = playlist_df_2.rename(columns = {'customer_id':'number of unique streamers'})

playlist_df_2

| number of unique streamers | |

|---|---|

| playlist_name | |

| SEPTEMBER 2016 TOP HITS | 14 |

| 2015 Hits | 2 |

| 2016 Rap ? | 5 |

| ?Space ? | 1 |

| Avicii - Tiësto - Calvin Harris - Alesso - Swedish house mafia - Zedd - Nause - David Guetta - Har | 1 |

| ... | ... |

| Éxitos de Hoy - Chile | 14 |

| Éxitos en acústico | 1 |

| Ö3-Hörerplaylist | 1 |

| Örnis Playlist | 1 |

| écouter | 2 |

7102 rows × 1 columns

# merge above dataframes

masta = pd.merge(playlist_df_1, playlist_df_2, right_index = True, left_index = True)

# create new column for playlist passion score

masta['Playlist Passion Score'] = (masta['Prior Playlist Stream Counts']/masta['number of unique streamers'])

masta

| Prior Playlist Stream Counts | number of unique streamers | Playlist Passion Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| artist_name | playlist_name | |||

| #90s Update | After Work House | 3 | 43 | 0.069767 |

| ENERGY - HIT MUSIC ONLY! | 1 | 31 | 0.032258 | |

| 17 Memphis | Wild Country | 6 | 192 | 0.031250 |

| 99 Percent | Musical.ly songs | 8 | 18 | 0.444444 |

| Party Bangers! | 8 | 139 | 0.057554 | |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| gnash | wake up playlist? | 1 | 4 | 0.250000 |

| we can hurt together | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | |

| work out playlist | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | |

| |Solo Dance - Martin Jensen|Setting Fire - The Chainsmokers|Castle on the Hill - Ed Sheeran|Shape of | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | |

| livetune+ | J-Track Makunouchi | 1 | 2 | 0.500000 |

18659 rows × 3 columns

# since we have individual passion scores for each playlist an artist shows up in, we can find the mean across these to have one metric per

# artist

# quantified playlist features dataframe

masta1 = masta.groupby('artist_name').agg({'Playlist Passion Score':np.mean})

masta1

| Playlist Passion Score | |

|---|---|

| artist_name | |

| #90s Update | 0.051013 |

| 17 Memphis | 0.031250 |

| 99 Percent | 0.458733 |

| A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie | 0.362968 |

| A Boogie Wit da Hoodie | 0.454769 |

| ... | ... |

| birthday | 0.500000 |

| dvsn | 0.498281 |

| flor | 0.189314 |

| gnash | 0.460517 |

| livetune+ | 0.500000 |

471 rows × 1 columns

3.3) User-base features

I can use the age and gender columns to create an audience profile per artist.

- Gender Percentage Breakdown

- Age vector quantization

Audience profile per artist by gender

data.loc[data.gender=="female","gender_binary"] = 1 #create new column and denote '1' if female

data.loc[data.gender=="male","gender_binary"] = 0 # denote '0' if male

gender_PER = data.groupby(['artist_name']).gender_binary.mean() #'mean' method gives percentage of women

# we omit including percentage of men to avoid perfect multicollinearity

gender_PER = DataFrame(gender_PER)

# clean up dataframe

gender_PER = gender_PER.rename(columns = {'gender_binary':'percentage of females'})

gender_PER = gender_PER.rename(columns = {'percentage of females':'percentage of female streamers'})

# merge the above to quantified artist features dataframe 'artist_df' and call the resulting dataframe 'final_df'

final_df = pd.merge(artist_df, gender_PER, right_index = True, left_index = True)

final_df = final_df.rename(columns = {'stream_count_per_artist':'stream cunt per artist', 'streamers_per_artist':'number of unique streamers per artist', 'passion-score_final':'passion score'})

final_df

| streams_count_per_artist | number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| artist_name | ||||

| Charlie Puth | 447873 | 367023 | 1.220286 | 0.578064 |

| Dua Lipa | 315663 | 260778 | 1.210466 | 0.594637 |

| Lukas Graham | 311271 | 247580 | 1.257254 | 0.480609 |

| Cheat Codes | 255820 | 225658 | 1.133662 | 0.547475 |

| Anne-Marie | 247934 | 220413 | 1.124861 | 0.602910 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Arsen | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| Helena Majdaniec | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 |

| Ugo | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 |

| Coraluna | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 |

| Deuspi | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 |

661 rows × 4 columns

In creating the above, I have not accounted for repeated streams by a female/male customer. This may give a misleading view of our per-artist gender profile. To double-check, I compare the gender split with repeated customers to that with unique customers

#with repeated streamers

num_male = len(data[data['gender']=='male'])

num_female = len(data[data['gender']=='female'])

percentage_male_repeat = (num_male/(num_male+num_female)*100)

percentage_female_repeat = (num_female/(num_male+num_female)*100)

print(percentage_male_repeat)

print(percentage_female_repeat)

48.05633457164355

51.94366542835645

unique_genders # taken from exploratory analysis

| Split | |

|---|---|

| gender | |

| female | 1076907 |

| male | 994741 |

#with unique streamers

total_unique_users = unique_genders.loc['female', 'Split'] + unique_genders.loc['male', 'Split']

percentage_female_unique = (unique_genders.loc['female', 'Split']/total_unique_users)*100

percentage_male_unique= (unique_genders.loc['male', 'Split']/total_unique_users)*100

print(percentage_male_unique)

print(percentage_female_unique)

48.01689283121457

51.98310716878544

There is a minimal difference between the gender splits with and without accounting for unique users. Our audience gender profile for each artist is valid.

Age vector quantisation

#Creating bins and labelling them

age_bins_df = data[["artist_name", "customer_id", "age"]]

age_bins_df = age_bins_df.drop_duplicates(subset = ['customer_id'])

bins = [0, 18, 25, 40, 70]

group_names = ['youth', 'young adult', 'adult', 'senior']

age_bins_df['age category'] = pd.cut(x=age_bins_df['age'], bins = bins, labels = group_names) # create bins out of intervals

age_bins_df = age_bins_df.set_index('artist_name') # turning into artist name level dataframe

age_bins_df.head()

| customer_id | age | age category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| artist_name | |||

| Sturgill Simpson | 6c022a8376c10aae37abb839eb7625fe | 49.0 | senior |

| Sturgill Simpson | 352292382ff3ee0cfd3b73b94ea0ff8f | 22.0 | young adult |

| Sturgill Simpson | c3f2b54e76696ed491d9d8f964c97774 | 25.0 | young adult |

| Sturgill Simpson | 6a06a9bbe042c73e8f1a3596ec321636 | 38.0 | adult |

| Sturgill Simpson | b2078313098854a18fec2d7dcb2b0d73 | 24.0 | young adult |

Next I find the number of (each age group) listeners per artist

# number of youths

youth = age_bins_df[age_bins_df['age category']=='youth']

youth_count = DataFrame(youth.groupby('artist_name')['age category'].count())

youth_count = youth_count.rename(columns = {'age category':'number of youths'})

# number of young adults

young_adult = age_bins_df[age_bins_df['age category']=='young adult']

young_adult_count = DataFrame(young_adult.groupby('artist_name')['age category'].count())

young_adult_count = young_adult_count.rename(columns = {'age category':'number of young adults'})

# number of adults

adult = age_bins_df[age_bins_df['age category']=='adult']

adult_count = DataFrame(adult.groupby('artist_name')['age category'].count())

adult_count = adult_count.rename(columns = {'age category':'number of adults'})

# number of seniors

senior = age_bins_df[age_bins_df['age category']=='senior']

senior_count = DataFrame(senior.groupby('artist_name')['age category'].count())

senior_count= senior_count.rename(columns = {'age category':'number of seniors'})

# merge into one dataframe

age_vect_df = pd.concat([youth_count, young_adult_count, adult_count, senior_count], axis = 1, sort = 'True').fillna(0)

age_vect_df

| number of youths | number of young adults | number of adults | number of seniors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #90s Update | 1.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 |

| 17 Memphis | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| 2D | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3JS | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 99 Percent | 327.0 | 353.0 | 169.0 | 115.0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| birthday | 5.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 0.0 |

| dvsn | 1775.0 | 7859.0 | 5334.0 | 1028.0 |

| flor | 17.0 | 37.0 | 35.0 | 10.0 |

| gnash | 16099.0 | 34695.0 | 26429.0 | 9214.0 |

| livetune+ | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 |

655 rows × 4 columns

Find each bin as a share of total streamers

age_vect_df['% of youth'] = age_vect_df['number of youths']/(age_vect_df['number of youths'] + age_vect_df['number of young adults'] + age_vect_df['number of adults'] + age_vect_df['number of seniors'])

age_vect_df['% of young adults'] = age_vect_df['number of young adults']/(age_vect_df['number of youths'] + age_vect_df['number of young adults'] + age_vect_df['number of adults'] + age_vect_df['number of seniors'])

age_vect_df['% of adults'] = age_vect_df['number of adults']/(age_vect_df['number of youths'] + age_vect_df['number of young adults'] + age_vect_df['number of adults'] + age_vect_df['number of seniors'])

age_vect_df['% of seniors'] = age_vect_df['number of seniors']/(age_vect_df['number of youths'] + age_vect_df['number of young adults'] + age_vect_df['number of adults'] + age_vect_df['number of seniors'])

# Age vectorised dataframe

share_streamers_by_age = age_vect_df[['% of youth', '% of young adults', '% of adults', '% of seniors']]

# Merge with final_df

final_df = pd.merge(final_df, share_streamers_by_age, right_index = True, left_index = True)

#drop % of seniors to avoid perfect multicollinearity

final_df = final_df.drop('% of seniors', axis = 1)

# Merge playlist featured dataframe with final_df

final_df = pd.merge(final_df, masta1, right_index = True, left_index = True)

final_df = pd.merge(final_df, successful, right_index = True, left_index = True)

final_df.head(2)

| streams_count_per_artist | number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlie Puth | 447873 | 367023 | 1.220286 | 0.578064 | 0.163328 | 0.383220 | 0.315179 | 0.564329 | 1 |

| Dua Lipa | 315663 | 260778 | 1.210466 | 0.594637 | 0.135952 | 0.385154 | 0.350957 | 0.375176 | 1 |

Principle Component Analysis

The data also contains a partial region code of the listener. We might want to consider including the regional breakdown of streams per artist as a feature of our model, to know if streams for certain regions are particularly influential on the future performance of an artist.

However, we have over 400 unique regions and like playlists, including them all would lead to too many features and a large sparse matrix. One way in which to extract relevant ‘generalized’ features of each region would be to incorporate census and demographic data, from publicly available datasets.

This is however beyond the scope of this project. Instead, a better way to summarize the impact of regional variation in streams is to use dimensionality reduction techniques. Here we will use Principle Component Analysis (PCA) to capture the regional variation in stream count.

PCA captures the majority of variation in the original feature set and represents it as a set of new orthogonal variables. Each ‘component’ of PCA is a linear combination of every feature, i.e. playlist in the dataset. Use scikit-learn’s PCA module (Pedregosa, et al., 2011) for generating PCA components.

# Create a copy of artist level dataframe

final_artist_level_data_copy = final_df.copy()

# clearn dataframe

final_artist_level_data_copy = final_artist_level_data_copy.rename(columns = {'artist_name_column':'artist_name'})

final_artist_level_data_copy['artist_name_column'] = final_artist_level_data_copy.index

#view data

final_artist_level_data_copy

| streams_count_per_artist | number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | artist_name_column | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlie Puth | 447873 | 367023 | 1.220286 | 0.578064 | 0.163328 | 0.383220 | 0.315179 | 0.564329 | 1 | Charlie Puth |

| Dua Lipa | 315663 | 260778 | 1.210466 | 0.594637 | 0.135952 | 0.385154 | 0.350957 | 0.375176 | 1 | Dua Lipa |

| Lukas Graham | 311271 | 247580 | 1.257254 | 0.480609 | 0.147844 | 0.389005 | 0.326037 | 0.519977 | 1 | Lukas Graham |

| Cheat Codes | 255820 | 225658 | 1.133662 | 0.547475 | 0.163556 | 0.456306 | 0.287889 | 0.427119 | 1 | Cheat Codes |

| Anne-Marie | 247934 | 220413 | 1.124861 | 0.602910 | 0.171681 | 0.391824 | 0.320438 | 0.325077 | 1 | Anne-Marie |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Tuah SAJA | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0 | Tuah SAJA |

| Hunter | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0 | Hunter |

| Many | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.500000 | 0 | Many |

| Arsen | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.055556 | 0 | Arsen |

| Deuspi | 1 | 1 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.333333 | 0 | Deuspi |

469 rows × 10 columns

Splitting data:

It is a good idea to split data at this point given we are about to embark on PCA analysis. I want the PCA method to be fit on the training set and to transform both training and test sets

#splitting data for PCA

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

Train_set_region_dataframe, test_set_region_dataframe = train_test_split(final_artist_level_data_copy, test_size = 0.3, shuffle = True, random_state = 42)

# get region codes per artist

def myFunc(streaming_data, artist_data, region_codes=[], training=False):

streaming_data = streaming_data.loc[streaming_data.artist_name.isin(artist_data.index),]

region_df = pd.DataFrame(streaming_data.groupby(["artist_name", 'region_code']).region_code.count())

if training:

region_codes = region_df.index.levels[1].values

#re-create a new array of levels, now including all artists and region codes

levels = [region_df.index.levels[0].values, region_codes]

new_index = pd.MultiIndex.from_product(levels, names = region_df.index.names)

#reindex the count and fill empty values with zero (NaN by default)

region_df = region_df.reindex(new_index, fill_value = 0)

region_df = pd.DataFrame(region_df).unstack()

region_df = region_df["region_code"]

region_df = region_df.reset_index()

if training:

return(region_codes, region_df)

else:

return(region_df)

training_region_codes_list, training_artist_region_dataframe = myFunc(data, Train_set_region_dataframe, training=True)

testing_artist_region_dataframe = myFunc(data, test_set_region_dataframe, region_codes=training_region_codes_list)

#region codes by artist for training data

training_artist_region_dataframe

| region_code | artist_name | 0 | 500 | 501 | 504 | 505 | 506 | 508 | 511 | 512 | ... | SE-AC | SE-BD | SE-E | SE-F | SE-H | SE-M | SE-N | SE-O | SE-S | SE-Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 17 Memphis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 99 Percent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | A Boogie Wit da Hoodie | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | A R I Z O N A | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 323 | Zac Brown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 324 | Zak Abel | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 325 | Zarcort | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 326 | Zion & Lennox | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 327 | gnash | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

328 rows × 464 columns

#executing PCA

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

train_regions_numerical = training_artist_region_dataframe.drop("artist_name",axis=1)

test_regions_numerical = testing_artist_region_dataframe.drop("artist_name",axis=1)

pca = PCA(n_components=10)

pca.fit(training_artist_region_dataframe.drop("artist_name",axis=1))

pca_region_df_train = pca.transform(train_regions_numerical)

pca_region_df_test = pca.transform(test_regions_numerical)

print("original shape: ", training_artist_region_dataframe.shape)

print("transformed shape:", pca_region_df_train.shape)

# dimensions have been reduced from 463 to 10

original shape: (328, 464)

transformed shape: (328, 10)

#making dataframes for training PCA set and test PCA set

PCA_df_train = pd.DataFrame(pca_region_df_train, columns=["PCA"+str(i+1)for i in range(10)])

PCA_df_train["artist_name"] = training_artist_region_dataframe["artist_name"]

PCA_df_test = pd.DataFrame(pca_region_df_test, columns=["PCA"+str(i+1)for i in range(10)])

PCA_df_test["artist_name"] = testing_artist_region_dataframe["artist_name"]

PCA_df_test.set_index('artist_name')

testing_artist_region_dataframe.set_index("artist_name")

| region_code | 0 | 500 | 501 | 504 | 505 | 506 | 508 | 511 | 512 | 513 | ... | SE-AC | SE-BD | SE-E | SE-F | SE-H | SE-M | SE-N | SE-O | SE-S | SE-Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| artist_name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| #90s Update | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AGWA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adan Carmona | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alex Roy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alexander Brown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Youngboy Never Broke Again | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| birthday | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| dvsn | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| flor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| livetune+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

141 rows × 463 columns

PCA_df_train.head(2)

| PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | PCA5 | PCA6 | PCA7 | PCA8 | PCA9 | PCA10 | artist_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -1066.030104 | -8.449366 | -21.765807 | -7.491672 | 4.317912 | -6.598770 | 1.340678 | -1.049194 | 0.060992 | 0.699383 | 17 Memphis |

| 1 | -876.608664 | -20.707568 | -33.802313 | -16.558912 | 0.168555 | -2.662221 | 1.100423 | 2.711004 | 0.515492 | -1.830186 | 99 Percent |

#PCA_df_train = training pca region df

#PCA_df_test = my test pca region df

#Train_set_region_dataframe = artist level master training dataframe

#test_set_region_dataframe = artist level master training dataframe

# Now we merge across the respective training and test dataframe pairs

PCA_df_train = PCA_df_train.set_index('artist_name') #turn artist name column into index

PCA_df_test = PCA_df_test.set_index('artist_name') #turn artist name column into index

#drop higher level indexing and clearn

training_artist_region_dataframe = training_artist_region_dataframe.rename_axis(None,axis=1)

training_artist_region_dataframe = training_artist_region_dataframe.set_index('artist_name')

#Make master training data set by merging artist level df and PCA df

master_train_set = pd.merge(Train_set_region_dataframe, PCA_df_train, right_index = True, left_index = True)

# clean up master training data set

master_train_set = master_train_set.drop('artist_name_column', axis = 1)

master_train_set = master_train_set.sort_index()

#view master training set

master_train_set.head(3)

| streams_count_per_artist | number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | PCA5 | PCA6 | PCA7 | PCA8 | PCA9 | PCA10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Memphis | 12 | 12 | 1.000000 | 0.666667 | 0.200000 | 0.400000 | 0.300000 | 0.031250 | 0 | -1066.030104 | -8.449366 | -21.765807 | -7.491672 | 4.317912 | -6.598770 | 1.340678 | -1.049194 | 0.060992 | 0.699383 |

| 99 Percent | 1291 | 1189 | 1.085786 | 0.677926 | 0.339212 | 0.366183 | 0.175311 | 0.458733 | 0 | -876.608664 | -20.707568 | -33.802313 | -16.558912 | 0.168555 | -2.662221 | 1.100423 | 2.711004 | 0.515492 | -1.830186 |

| A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie | 9904 | 7713 | 1.284066 | 0.273748 | 0.191162 | 0.516763 | 0.233999 | 0.362968 | 0 | 1195.401131 | 468.282362 | 222.532572 | 17.367009 | -5.795103 | -16.910525 | 28.538175 | 19.079896 | 12.250924 | -21.050765 |

#Make master test data set

master_test_set = pd.merge(test_set_region_dataframe, PCA_df_test, right_index = True, left_index = True)

master_test_set = master_test_set.sort_index()

master_test_set = master_test_set.drop('artist_name_column', axis = 1)

Check the PCA feature table to make sure the dataframe looks as expected. Comment on anything the looks important.

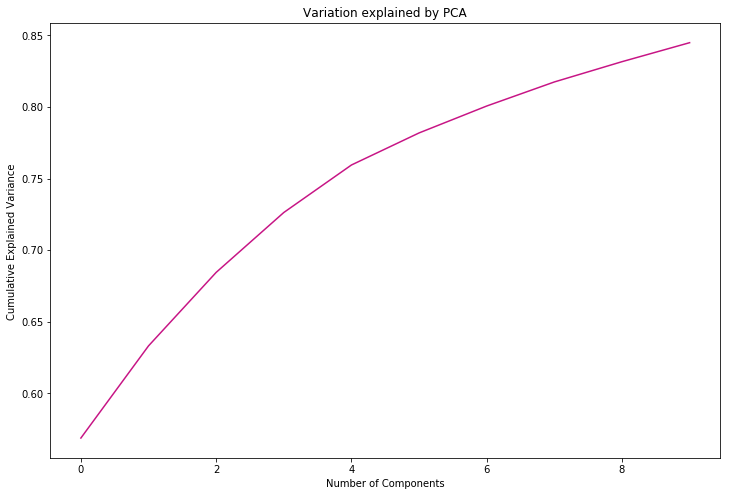

I want to now check which components of PCA explain the majority of variation in the data. Accordingly, I will use only those components in my further analysis.

#turn PCA training data into numpy array

X = np.array(training_artist_region_dataframe)

#Standardise the above array

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

X = scaler.fit_transform(X)

#execute PCA on standardised array

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca = PCA(n_components=10, svd_solver='full')

pca.fit(X)

PCA_transformed = pca.transform(X)

PCA_transformed

array([[-3.24487688e+00, 2.23194039e-01, -2.89613207e-01, ...,

-2.23460798e-01, -1.24027489e-01, -3.20760809e-02],

[-2.67729911e+00, 4.65771526e-01, -2.46052532e-01, ...,

-2.64969502e-01, -1.22233948e-01, -2.90802672e-03],

[-3.04274242e-03, 6.98425294e-01, 3.87738721e-01, ...,

-7.42768455e-01, -1.07078913e-01, 2.72905852e-01],

...,

[-3.11129096e+00, 1.48170675e-01, -3.45356825e-01, ...,

7.37797187e-01, -6.06759708e-01, 6.70258585e-01],

[ 7.68764821e+00, -1.07771150e+01, 3.14785696e+00, ...,

4.41358985e+01, -1.04955601e+01, 4.08527873e+00],

[ 6.56496939e+01, 2.48349051e+01, 4.94583939e+00, ...,

3.11551215e+00, -5.43103814e+00, 1.98020367e+01]])

sum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_)

# our chosen n= 10 dimensions explain 84% of variation. This is visualised below.

0.8449580172954606

#visualise PCA-explained variation

plt.plot(np.cumsum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_), color = 'mediumvioletred')

plt.xlabel('Number of Components')

plt.ylabel('Cumulative Explained Variance ')

plt.title('Variation explained by PCA')

# interestingly, 4 components explained just over 75% of variance

Text(0.5,1,'Variation explained by PCA')

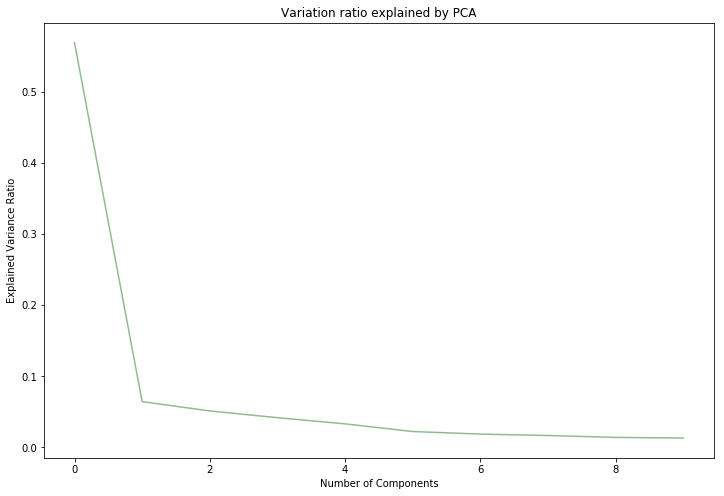

plt.plot((pca.explained_variance_ratio_), color = 'darkseagreen')

plt.xlabel('Number of Components')

plt.ylabel('Explained Variance Ratio')

plt.title('Variation ratio explained by PCA')

Text(0.5,1,'Variation ratio explained by PCA')

Feature Transformation

I considered whether feature transformation on particular features such as influence, gender breakdown and age breakdown would be useful. Having explored transforming various features, I find that no transformation was particularly useful, and omitted the analysis to save space.

Preprocessing

Before we can run any models on our dataset, I must make sure it is prepared and cleaned to avoid errors in results. This stage is generally refered to as preprocessing.

To begin with, I need to deal with missing data in the dataframe - the ML algorithm will not be able to process NaN or missing values.

For this study, we will be imputing missing numerical values, and filling any one which we were not able to imput, with 0.

# Handle missing values using imputer. Execute imputer separately on master training and test dataframes

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

#for master train set

impute = Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='mean', axis=1)

df_imputer_train = pd.DataFrame(impute.fit_transform(master_train_set))

df_imputer_train.columns = master_train_set.columns

df_imputer_train.index = master_train_set.index

df_imputer_train.head()

/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/sklearn/utils/deprecation.py:66: DeprecationWarning: Class Imputer is deprecated; Imputer was deprecated in version 0.20 and will be removed in 0.22. Import impute.SimpleImputer from sklearn instead.

warnings.warn(msg, category=DeprecationWarning)

| streams_count_per_artist | number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | PCA5 | PCA6 | PCA7 | PCA8 | PCA9 | PCA10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Memphis | 12.0 | 12.0 | 1.000000 | 0.666667 | 0.200000 | 0.400000 | 0.300000 | 0.031250 | 0.0 | -1066.030104 | -8.449366 | -21.765807 | -7.491672 | 4.317912 | -6.598770 | 1.340678 | -1.049194 | 0.060992 | 0.699383 |

| 99 Percent | 1291.0 | 1189.0 | 1.085786 | 0.677926 | 0.339212 | 0.366183 | 0.175311 | 0.458733 | 0.0 | -876.608664 | -20.707568 | -33.802313 | -16.558912 | 0.168555 | -2.662221 | 1.100423 | 2.711004 | 0.515492 | -1.830186 |

| A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie | 9904.0 | 7713.0 | 1.284066 | 0.273748 | 0.191162 | 0.516763 | 0.233999 | 0.362968 | 0.0 | 1195.401131 | 468.282362 | 222.532572 | 17.367009 | -5.795103 | -16.910525 | 28.538175 | 19.079896 | 12.250924 | -21.050765 |

| A Boogie Wit da Hoodie | 13264.0 | 11154.0 | 1.189170 | 0.318605 | 0.279433 | 0.437202 | 0.199237 | 0.454769 | 1.0 | 326.689102 | -507.510048 | 478.979715 | -84.016157 | -57.294053 | 18.983290 | -33.768814 | 31.422452 | 7.235614 | 34.985667 |

| A R I Z O N A | 68830.0 | 58987.0 | 1.166867 | 0.521963 | 0.129727 | 0.402716 | 0.355355 | 0.333574 | 1.0 | 9160.499942 | -584.878448 | 93.611835 | 573.275760 | -214.647777 | 234.952019 | 41.561658 | -87.234877 | 296.069304 | -114.536150 |

#for master test set

#impute = Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='mean', axis=1)

df_imputer_test = pd.DataFrame(impute.fit_transform(master_test_set))

df_imputer_test.columns = master_test_set.columns

df_imputer_test.index = master_test_set.index

df_imputer_test = df_imputer_test.drop('streams_count_per_artist', axis = 1)

df_imputer_test.head()

| number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | PCA5 | PCA6 | PCA7 | PCA8 | PCA9 | PCA10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #90s Update | 15.0 | 1.066667 | 0.437500 | 0.076923 | 0.230769 | 0.615385 | 0.051013 | 0.0 | -1064.361806 | -7.434001 | -21.618842 | -7.202030 | 4.095893 | -6.748749 | 0.933668 | -0.872956 | -0.396088 | 0.447215 |

| AGWA | 3.0 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.200000 | 0.0 | -1067.217986 | -8.295809 | -21.709381 | -7.976221 | 4.467162 | -6.415712 | 0.415944 | -0.607453 | 0.057300 | 1.009670 |

| Adan Carmona | 12.0 | 1.166667 | 0.500000 | 0.000000 | 0.222222 | 0.777778 | 0.170635 | 0.0 | -1063.787393 | -6.420513 | -21.857666 | -7.174886 | 4.471635 | -6.026823 | 0.357345 | -0.898505 | -0.177646 | 0.599773 |

| Alex Roy | 3.0 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.170635 | 0.0 | -1066.488811 | -7.641579 | -21.857347 | -7.617523 | 4.423573 | -6.285065 | 0.398114 | -0.771238 | 0.016631 | 0.754984 |

| Alexander Brown | 141.0 | 1.042553 | 0.369863 | 0.022727 | 0.257576 | 0.553030 | 0.118699 | 0.0 | -1028.173626 | 2.066334 | -21.525637 | -3.827187 | 4.449258 | -4.086906 | 3.009670 | -1.857250 | 1.357304 | 0.889887 |

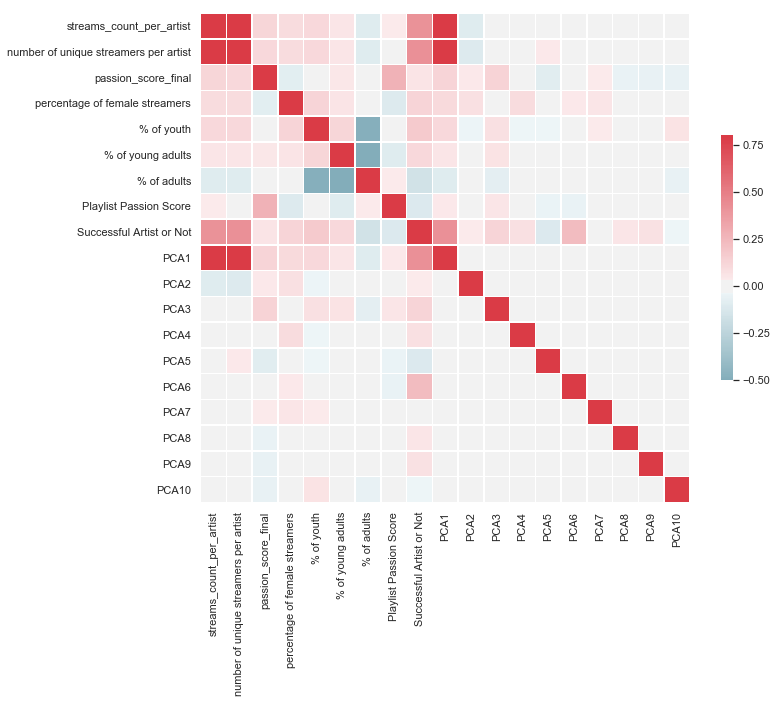

Next, we need to make sure that none of the variables going into the model are collinear, and if so, we need to remove those variables that are highly correlated.

Multi-collinearity

I will check and deal with multi-collinearity in my feature set.

# We can create a correlation matrix to better understand the correlations between variables, as opposed to just viewing raw figures

import seaborn as sns

sns.set(style="whitegrid")

# Compute the correlation matrix

training_corr = df_imputer_train.corr()

# Set up plot figure

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(11, 9))

# Generate custom diverging colormap

cmap = sns.diverging_palette(220, 10, as_cmap=True)

# Draw heatmap

sns.heatmap(training_corr, cmap=cmap, vmin = -0.5, vmax=0.8, center=0, square=True, linewidths=.5, cbar_kws={"shrink": .5})

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a1fe0e1d0>

I see that stream count per artist is highly correlated with PCA1 and number of unique streamers per artist. I will drop this variable.

Other than that, there are no particulary strong correlations we need to be worried about

df_imputer_train = df_imputer_train.drop('streams_count_per_artist', axis = 1)

Finally, we want to take a look out the class balance in our dependent variable.

Given the natural bias in our data, i.e. there are more cases of failure than of success in the training and test sets; there is a strong bias toward predicting ‘failure’. Based on our complete (unbalanced classes) training sample, if the model only predicted ‘failure’, we would achieve an accuracy of 88.8%.

To give us a more even class balance, without losing too much data, we will sample data from the bigger class to achive a class balance closer to 60-40.

There is another way to determine the accuracy of our predictions using a confusion matrix and ROC curve, but more on that later. For now, we will go ahead with sampling the bigger class:

Sampling Techniques and why they are necessary

In my master training set, 40% of our cases must be successful, and the remaining 60% unsuccessful. Given that, after the train-test split, we have 53 successful artists in our training set, our unsuccessful artists must be [(53/0.4) - 53] = 80. We can obtain a random sample to get these 80 artists.

However, the problem we face here would be that the training sample would be too small, and will likely perform poorer than if the sample size were larger. To get around this problem, we can oversample the minority class. I conduct this below

ultimate_unsuccessful = df_imputer_train[df_imputer_train['Successful Artist or Not'] == 0] # unsuccessful unique artists

ultimate_successful = df_imputer_train[df_imputer_train['Successful Artist or Not'] == 1] # successful unique artists

ultimate_ultimate_train = pd.concat([ultimate_successful, ultimate_unsuccessful]) #get all unique artists from master imputer training data set

# Create class count

count_class_boo, count_class_woo = ultimate_ultimate_train['Successful Artist or Not'].value_counts()

# Subdivide by class

df_class_boo = ultimate_ultimate_train[ultimate_ultimate_train['Successful Artist or Not']==0]

df_class_woo = ultimate_ultimate_train[ultimate_ultimate_train['Successful Artist or Not']==1]

#oversample minority class (Success == 1)

df_class_woo_oversampled = df_class_woo.sample(count_class_boo, replace = True)

ultimate_train_df = pd.concat([df_class_boo, df_class_woo_oversampled], axis = 0)

print(ultimate_train_df['Successful Artist or Not'].value_counts())

1.0 276

0.0 276

Name: Successful Artist or Not, dtype: int64

Now we have a much better dataset in terms of its size and class balance. Of course, there is the possibility that by oversampling from the minority (successful) class, I may have increased the chances of overfitting. If this is the case, then my model will perform poorly. The following steps will yield the answer to this predicament

4) Evaluate algorithms

Model Selection

There are number of classification models available to us via the scikit-learn package, and we can rapidly experiment using each of them to find the optimal model.

Below is an outline of the steps we will take to arrive at the best model:

- Split data into training and validation (hold-out) set

- Use cross-validation to fit different models to training set

- Select model with the highest cross-validation score as model of choice

- Tune hyper parameters of chosen model.

- Test the model on hold-out set

ultimate_train_df.head(2)

| number of unique streamers per artist | passion_score_final | percentage of female streamers | % of youth | % of young adults | % of adults | Playlist Passion Score | Successful Artist or Not | PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | PCA5 | PCA6 | PCA7 | PCA8 | PCA9 | PCA10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Memphis | 12.0 | 1.000000 | 0.666667 | 0.200000 | 0.400000 | 0.300000 | 0.031250 | 0.0 | -1066.030104 | -8.449366 | -21.765807 | -7.491672 | 4.317912 | -6.598770 | 1.340678 | -1.049194 | 0.060992 | 0.699383 |

| 99 Percent | 1189.0 | 1.085786 | 0.677926 | 0.339212 | 0.366183 | 0.175311 | 0.458733 | 0.0 | -876.608664 | -20.707568 | -33.802313 | -16.558912 | 0.168555 | -2.662221 | 1.100423 | 2.711004 | 0.515492 | -1.830186 |

We must turn our training and test data into arrays, which can be used in our classifiers

y_train = pd.DataFrame(ultimate_train_df['Successful Artist or Not'])

y_train = y_train.values

x_train = pd.DataFrame(ultimate_train_df.drop('Successful Artist or Not', axis = 1))

x_train = x_train.values

x_test = pd.DataFrame(df_imputer_test.drop('Successful Artist or Not', axis = 1))

x_test = x_test.values

y_test = pd.DataFrame(df_imputer_test['Successful Artist or Not'])

y_test = y_test.values

Now we will loop through different classifiers and compute the cross-validation score of each. This will determine the best performing model, which we can then target for hyperparameter tuning

from sklearn import model_selection

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, log_loss

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.svm import SVC, LinearSVC, NuSVC

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier, GradientBoostingClassifier

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import QuadraticDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

#choose classifiers to test

classifiers = [

KNeighborsClassifier(),

SVC(kernel="rbf", C=0.025, probability=True, gamma ='scale'),

NuSVC(probability=True, gamma ='scale'),

DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state = 42),

GaussianNB(),

LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(),

LogisticRegression(),

RandomForestClassifier()]

# make a dataframe to display outputs

log_cols=["Classifier", "Accuracy"]

log = pd.DataFrame(columns=log_cols)

# test each classifier in turn

for clf in classifiers:

model = clf.fit(x_train, y_train)

name = clf.__class__.__name__

kfold = model_selection.KFold(n_splits=10, random_state=7)

score = model_selection.cross_val_score(model, x_train, y_train, cv=kfold)

m_score = np.mean(score)

log_entry = pd.DataFrame([[name, m_score*100]], columns=log_cols)

log = log.append(log_entry)

log.index = range(len(log))

log

| Classifier | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | KNeighborsClassifier | 85.363636 |

| 1 | SVC | 10.181818 |

| 2 | NuSVC | 79.834416 |

| 3 | DecisionTreeClassifier | 94.782468 |

| 4 | GaussianNB | 81.103896 |

| 5 | LinearDiscriminantAnalysis | 65.383117 |

| 6 | LogisticRegression | 82.207792 |

| 7 | RandomForestClassifier | 95.850649 |

# plot results for easier understanding

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

sns.set_color_codes("bright")

sns.barplot(x='Accuracy', y='Classifier', data=log)

plt.xlabel('Accuracy %')

plt.title('Cross Validation Score by classifier')

plt.show()

Best classifier:

The best classifier is Random Forests, with a cross-validation score of 96%, which is very impressive. I can attempt to tune it further, but even if I am unable to improve its performance significantly, the model’s current performance is good enough to be tested on the test set

5) Improve Results

Hyper Parameter Tuning

I will perform hyperparameter turing and demonstrate improved performance and comment on any specific behaviour of my chosen classifier and set out the final structure and parameter settings.

# Using grid search to iterate through combinations of hyperparameter values for Random Forests

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

#chosen parameters to manipulate

parameter_grid = {'bootstrap': [True, False], 'max_depth': [int(x) for x in np.linspace(1, 18, num = 11)], 'max_features':['auto', 'sqrt'],

'n_estimators':[int(x) for x in np.linspace(start = 20, stop = 200, num = 10)], 'min_samples_split':[2, 5, 10],

'min_samples_leaf':[1, 2, 4]}

RF = RandomForestClassifier(random_state = 42)

# execute grid search

grid_search = GridSearchCV(estimator = RF, param_grid = parameter_grid, cv = 3, n_jobs = -1, verbose = 2)

# show CV score

print('Random Forests CV score: ')

grid_search.fit(x_train, y_train)

print(grid_search.best_params_) # show best parameters

print(grid_search.best_score_) # display score associated with said parameters

Random Forests CV score:

Fitting 3 folds for each of 3960 candidates, totalling 11880 fits

[Parallel(n_jobs=-1)]: Using backend LokyBackend with 8 concurrent workers.

[Parallel(n_jobs=-1)]: Done 25 tasks | elapsed: 2.3s

.

.

.

[Parallel(n_jobs=-1)]: Done 11689 tasks | elapsed: 7.1min

{'bootstrap': False, 'max_depth': 9, 'max_features': 'auto', 'min_samples_leaf': 1, 'min_samples_split': 10, 'n_estimators': 60}

0.9710144927536232

[Parallel(n_jobs=-1)]: Done 11880 out of 11880 | elapsed: 7.2min finished

Hyperparameter tuning has led to an increase in cross-validation score of 0.7% approximately. Since the model performed well in the first place, we should not be too worried about this insignificant magnitude of increase

# Run the model again, this time manually inputting the best parameters found by the grid search to confirm the cross validation score

RF1 = RandomForestClassifier(random_state = 42, bootstrap = False, max_depth = 11, max_features = 'auto', min_samples_leaf =1

,min_samples_split = 2, n_estimators = 40)

kfold_RF = model_selection.KFold(n_splits=10, random_state=42) # 10 folds

cv_result_RF = model_selection.cross_val_score(RF1, x_train, y_train, cv=kfold)

print("CV score: {:.4%}".format(cv_result_RF.mean())) # print mean of CV scores across 10 folds

CV score: 97.8377%

Ensemble modeling

I will now build an ensemble model and demonstrate improved performance. I will comment on specific behaviour of my chosen classifier and set out the final structure and parameter settings.